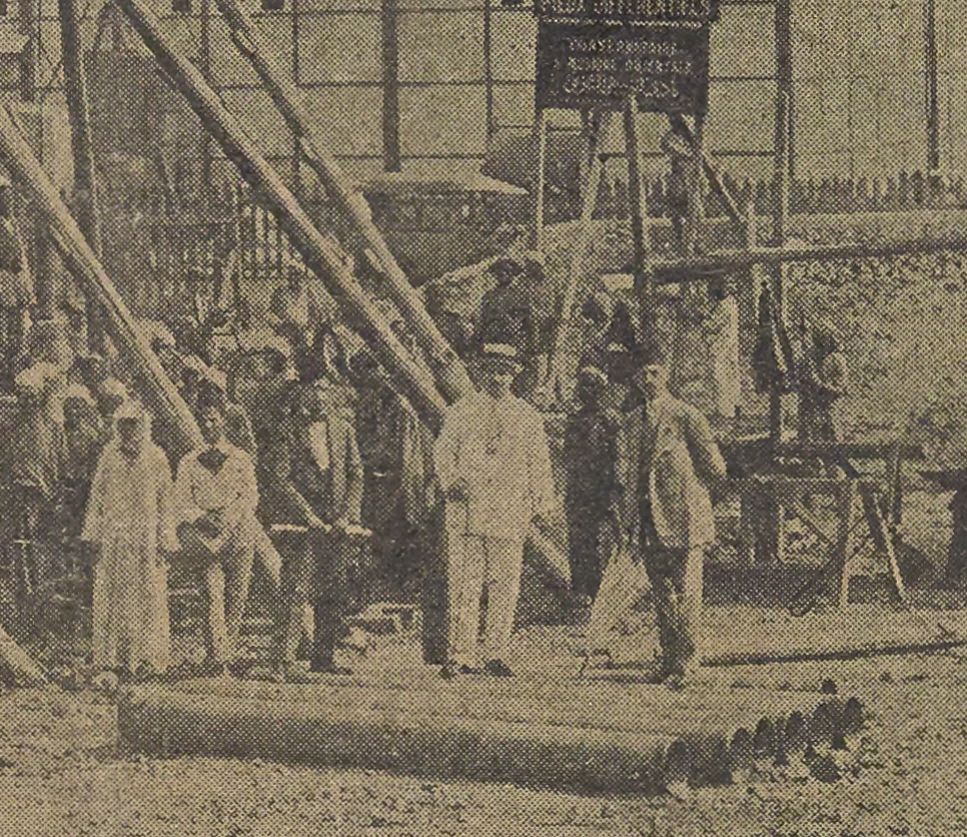

This image shows the construction site of Nadi al-Musiqa al-Sharqi (The Oriental Music Club) in 1921, which soon became al-Ma’had al-Malaki li-l-Musiqa al-‘Arabi (The Royal Institute of Arab Music) and today al-Ma’had al-‘Ali li-l-Musiqa al-‘Arabiyya (The Higher Institute of Arab Music) in Cairo, today located between the Nasser and ‘Urabi metro stations. In 1921, Sultan Fuad ordered the construction of this club (although it had been discussed among the elite Egyptian enthusiasts of Arab music since the 1900s). It was inaugurated with some pomp and rejoicing in 1923, and later served as the location of the famous 1932 “Oriental music” conference. Despite the importance of this building to the history of music and Orientalism, the remarkable fact is that this is a rare photograph about construction workers.

We can see in another photograph the nameless construction brigade, apparently from the countryside. In the first one, the journal captioned the engineer D. Limongelli, who was the construction contractor (muqawil) in white clothes, Faraj Efendi Amin (engineer at the Palaces), and Ya‘qub ‘Abd al-Wahhab Bey, the first director of the club. (They liked to be photographed together during the construction).

Since the mid-nineteenth century, official construction work for government purposes in Cairo, it appears, was largely in the hands of Italian and Greek entrepreneurs who worked in cooperation with Egyptian, Italian, Austro-Hungarian, and French engineer-architects, and hired Egyptian, cheap workforce from villages. Many had wood-workshops in Bulaq. While the architects are now well-known (Volait, 2005), the construction companies and entrepreneurs, and the construction workers themselves are completely left out of class-based histories of Egyptian workers (Goldberg, 1986; Beinin-Lockman, 1997; Hammad, 2016). Construction until today remains the most important labour, although non-industrialized, in Cairo and the countryside. The contractors, and in fact Limongelli, are also important in understanding the organization of work, the question of expertise, Euro-Ottoman-Egyptian elite society, and the everyday flow of capital. Limongelli, for instance, was a member of the Institut égyptien (later Institut d’Égypte), with many other important figures in the urban history of Cairo such as Ya’qub Artin Pasha, ‘Ali Bey Bahgat, and Herz Pasha. It is here that Limongelli gave a talk in 1919 about the best methods to create an amphiteatrum that all spectators can see at the same time, which likely led to his commission of constructing the Oriental Music Club in 1921 (Le Génie civil, 24 April 1920, 401).

Bibliography:

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.