By Sandie Blaise

I went to the movie theater on Wednesday and finally saw “12 Years a Slave.” For those of you who haven’t seen it yet, it is the story of Solomon Northup, a free black man working as a musician in the state of New York, who got kidnapped in Washington D.C. in 1841 and sold into slavery in the southern states. The movie is an adaptation of Solomon Northup’s memoirs, 12 Years a Slave, written in 1853. You can see the trailer here:

Beyond the actors’ performances and the movie itself – I hope they will win Academy Awards for such achievements – I wanted to talk about one of the points touched upon in the movie; the free black men abduction, and the way it reiterates the Middle Passage experience with the Mississippi River as an echo of the Atlantic Ocean.

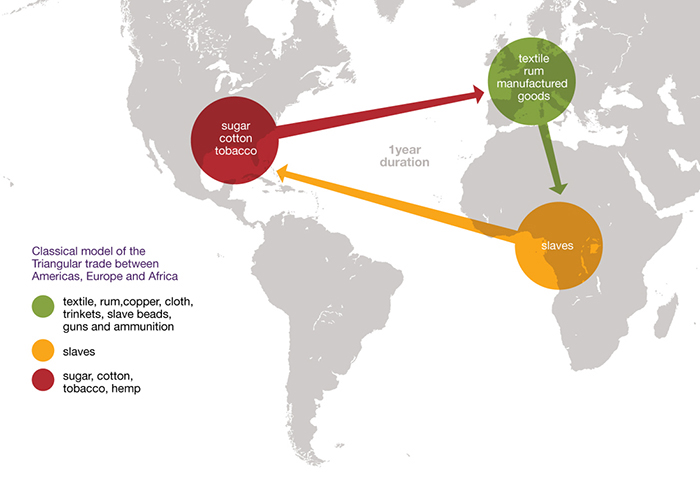

After the Middle Passage and its circular trans-Atlantic trajectory bringing slaves from the coast of Africa to Brazil, the Caribbean or the United States, before circling back to Europe with goods and then Africa to start over again, the Second Middle Passage refers to the domestic slave trade as a second forced migration within the United States.

Out of the 12 millions of slaves taken from Africa, about 250,000 were transported to the U.S.. After the slave trade ended in 1808, the U.S. was the only slave society in which slavery continued to develop naturally; slaves’ children were automatically enslaved when they were born, which increased slave population to 4 millions. The growth of the cotton industry led to the internal migration of slaves from the upper South to the lower South; indeed, from 1.5 million pounds of cotton produced in 1790, the country jumped to 35 million in 1800, 331 million in 1830 and had reached 2,275 million before the Civil War (see Ronald Bailey, “The Other Side of Slavery: Black Labor, Cotton, and Textile Industrialization in Great Britain and the United States,” Agricultural History, vol. 68, No. 2. Spring 1994).

This domestic slave migration dictated by the growth of the cotton industry shows how slavery cannot be separated from capitalism. Indeed, since cotton was an incredibly wanted good in the world; the cotton tended by slaves allowed planters to make money, so the more cotton planters wanted to grow, and the more slaves they needed to hand-pick it. Slaves were used as commodities by planters, but were also part of the Northern industrialists’ desire for profit too since by planting, tending and harvesting cotton, they were the first link of the industrial chain. They were the labor used to fulfill both planters and industrialists’ desire for profit. By moving down from the upper to the lower south where goods produced by slaves were sent to the north, the slave trade trajectory of the second Middle Passage reveals to be almost circular, too.

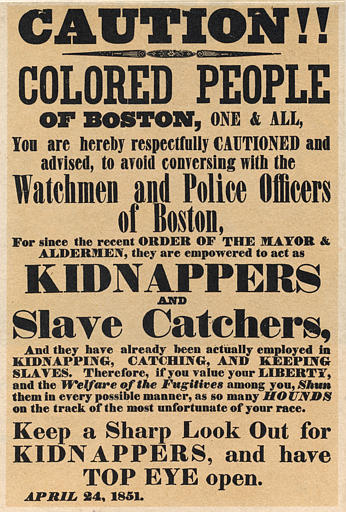

In “12 Years a Slave,” the abduction of free black men turns into what I would call a third, or an additional Middle Passage experience. After the slave trade officially stopped, and with the industrial growth of the cotton industry, slaves became a valued commodity. Slaves who had escaped slavery or former slaves who had bought their freedom and their descendants in the Northern states, like Solomon Northup, were considered free as long as they could show proof of their freedom. However, in 1793, the Fugitive Slave Act that had given effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the right of a slaveholder to recover an escaped slave. Therefore, any black person unable to show free papers could be considered a fugitive, and the person supposedly bringing them in would receive money. In 1850, a second Fugitive Slave Law was enforced, stating that fugitives could not testify in their own behalf, and that no trial by jury was provided. As an effect of capitalism serving personal profit, one can easily see why the abduction of free black people developed in the Northern states. Here is an example of a poster warning free “colored people” against kidnappers in Massachusetts:

There were several cases of African Americans who had escaped slavery and lived as free men before being kidnapped and sold back into slavery; Thomas Sims, Shadrach Minkins, the Garner families, Anthony Burns, among too many others. Even though Solomon Northup was born a free man and never had to work as a slave, his story identifies him as one of them.

In the movie, one of the scenes that struck me – among many others – was when, after kidnapping Northup and other African Americans, they board a ship and sail on the Mississippi towards Louisiana. Their journey on the Mississippi River strongly reminded me of the trans-Atlantic one that their parents or ancestors had lived. Both generations experienced a brutal separation from their families and land and a manifold process of dehumanization. The presence of chains around their ankles and wrists, and sometimes even muzzles on their faces turned them into commodities, and changing their names – when sold into slavery, Solomon becomes “Platt” – denied them agency through identity, further turning them into the planters’ property.

The abducted free men also had to experience traumatic conditions on board, and the murder of one of them followed by the decision to drop him into the water while they kept sailing towards an unknown destination strongly reminded me of the trans-Atlantic journey. At their arrival, they were exhibited naked or showing their talent (playing an instrument for instance) to future buyers who could examine them like animals or objects, hence repeating the experience they or their parents had lived at their arrival in America. This “third” Middle Passage, however, was somewhat different from the trans-Atlantic one in that even though African Americans on board probably did not know exactly where they were going, they still knew what they were going to do there. They had no illusion that slavery was what awaited them.