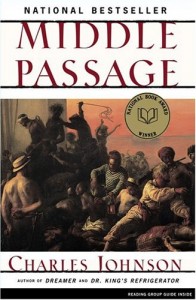

I’d like to compare a couple different literary approaches to narrating the experience of the Middle Passage. Charles Johnson’s Middle Passage offers an account with a distinct, and interesting narrative. Instead of choosing the kind of non-narrative, experimental form used in the poem Zong!, Johnson speaks through the mouth of a freed slave, born in the US, and previously owned by a relatively civil master in Indiana. His name is Rutherford Calhoun.

The novel tracks Rutherford’s journey on an illegal slave ship as it makes its journey from New Orleans to Africa and back again in the early 1830s. He originally finds himself on the ship as a way of avoiding his debts and an impending marriage, and so in many ways, feels bound to the ship in a way not unlike slavery. And in fact, that was one of the reasons that I enjoyed this novel so much; it manages to simultaneously teach the reader something about the awfulness that was the Atlantic slave trade, while simultaneously managing to remind the reader o all his own bonds, whether financial, societal, or marital, which act their own kind of very small slavery on the lives of any person.

This relatability is the key difference between this work and Zong!. Where the poem absolutely rejects narrative, the novel embraces it wholeheartedly, as Rutherford himself is writing it in order to preserve his memories of the ill-fated ship. That narrative allows the reader to very comfortably fit himself into the novel, to track his own way through Rutherford’s shoes. And that is the beauty of the character himself; as he is a total outsider to any of the societies in which we see him, he is forced to describe them in the most basic of terms, allowing the reader the needed education without taking on a tone of lecturing. This relatability then translates into the reader quickly making his way through the novel, and enjoying it all the way. If the goal of the novel is to remind and teach about the horrible history of this shipping channel, then it would seem that Jonson’s novel very successfully treads the line between weightiness and readability, appealing to a wide swath of readers.

I understand that the goal for Zong! was in some ways very different. Philip admits openly that she embraced the idea of a non-narrative as it was, to her, the only appropriate way to memorialize the slaves who had been thrown overboard during the Zong’s journey. As the poem quickly moves from semi-coherence into total chaos, I find that the effectiveness of the poem to effectively attract readers as well as memorialize is more limited. Yes, there might be meaning in piecing together word fragments that may ultimately provide some satisfaction, but the exercise is laborious. The reader finds himself (or at least I found myself) guiltily skimming through the last pages, which for the most part are nearly identical from one to the next for the last fifty or so, before briefly pausing to more closely consider the faded text, only to realize its utter incomprehensibility. We end exhaustedly with Philip’s own journal of her thoughts and feelings as she wrote, and at that point we just want it to be over.

As a memorial, perhaps the poem serves its purpose perfectly, capturing the exact lack of voice that those who died were given. If the poem could somehow stand in a physical place, visited by tourists with reverence, then I could see it as something a little more successful. But it isn’t purely monumental. It is a book, and as a book, it needs a reader in order to be experienced. While readers have no doubt appeared, if the goal of a memorial piece of literature is to maximize the number of people who learn and remember, then this seems to be a poem that will swiftly fall into unremembered history itself. And while it might genuinely be a good piece of poetry, I can’t help but deem it unsuccessful if it isn’t going to be remembered.

That said, Johnson’s book might be criticized for not taking the issue of the countless number killed in the passage seriously enough. he frames the book almost as a satire, and while the novel has its serious moments and themes, one would be hard pressed to call it a depressing read. And while it doesn’t necessarily memorialize any one group of slaves brought to the Americas, it doesn’t necessarily adopt a voice for them either. The slaves on-board Rutherford’s ship are of a fictional tribe, created by Johnson. Their fictitious nature seems to stand in then for all those brought across the Atlantic. They are mystical and for the most part silent. Only three or four of a couple hundred are given voice, and that silence seems to speak for all those who were forced through that horrible journey.

The novel, as a piece of fiction, is of course allowed more imagination than Philip’s more historical reconstruction (particularly when she has bound herself to such a limited dictionary of language). With that, Johnson is able to give th reader some sense of justice through the destruction of the ship. While nearly all the slaves as well as the crew die, at least it was not just slaves as it no doubt historically was. This justice though may most erode the value of the novel as a simultaneous memorial and fictive piece. Zong! so effectively captures the feeling of total tragedy, where Middle Passage somewhat skirts it. Yes, the plight of the slaves is recounted, but they are not our focus. We are not forced to uncomfortably experience any of the mental chaos they felt; instead our minds are happily satiated by the taming and tempering of Rutherford’s personality, ending with his marriage to his previously fled from fiance. The end is too tidy, and invites comfortable meaning of just the sort that Philip rejects.

At the end of the day, Middle Passage will draw more readership. It is simply more accessible. Hopefully readers will bring with them the level of thought to reject the simple emotional satiation in favor of a deeper sense of the tragedy of the Middle Passage itself. But even if read without that level of awareness, I believe the novel is still a more capable memorial than Zong!, and while I’m glad I read both, I would only recommend the novel to a friend.

I think that the way you’ve added the question of accessibility to the discussion in helpful, Thayne. It’s another element that acts of remembrance must take into account. I’m particularly interested in the fact that you argue Zong! is more effective in capturing the sense of the tragedy, whereas the novel “skirts it,” but nevertheless conclude that the latter is “a more capable memorial.” That’s not where I thought your argument was headed. Does the accessibility of the novel so far outweigh the critique of it you offer, not to mention the effectiveness of Zong!? Isn’t the inaccessibility of the poetry very much part of its purpose, as I think you suggest? I take your point that the different reading experiences will be a factor in reception. I wonder if there’s some sort of 2 coordinate axis here, with a text able to go wrong, so to speak, along either. On one axis we can plot whether or not the text does justice to the moral questions of what it represents. On the other we can ask if it is the kind of thing a reader will return to, or even recommend to a friend. Regardless, it’s helpful to think about accessibility as one of the factors in determining the efficacy of a memorial.