GO BACK TO “WORLD CUP 2014” PAGE

GO BACK TO “2010 SOUTH AFRICA WORLD CUP” PAGE

This page by Ramsey Al-Khalil

Lives of the Vuvuzela and Jabulani; Emergence of the Caxirola and Brazuca

Much of the talk during the 2010 FIFA World Cup wasn’t actually about soccer. Rather, vuvuzelas and the Jabulani ball created much larger domains for debate and discussion.

The vuvuzela is an instrument that South Africans claimed represented an importance part of their culture. “According to Enoch Mthembu, the public relations officer for the KwaZulu-Natal-based Shembe Church, the vuvuzela is an instrument that originated with his brethren at the dawn of the 20th century” (Wyatt). It was played alongside drums when they danced and worshipped God; it was also used to heal sick people, as the members of church used the trumpet more “constructively” than soccer fans nowadays do. The horn’s first appearance in football dates back to the 1980s at matches played by the Zulu Royals. Many of the fans were supposedly members of the Shembe Church and thus enthusiastically blasted the instruments for the duration of the match. Players welcomed the gesture, as they believed “it gave us an advantage, it changed the whole mood and vibe of the stadium” (Wyatt). Once manufacturing companies trademarked the name “vuvuzela” and began selling them commercially in that late 1990s, their use spread across the nation. Consequently, the horn’s popularity and importance to South Africans led to its use being permitted during 2010 FIFA World Cup matches. However, this did not occur without plenty of backlash from players, managers and at-home spectators. Had they been banned from competition, you wouldn’t have heard many complaints from those directly involved with the competition. Even so, the perception of these sorts of accessories is mixed, particularly from the players themselves. High-profile players, notably Patrice Evra and Cristiano Ronaldo, blamed vuvuzelas for players’ inability to concentrate. Conversely, others, namely Jamie Carragher, found them amusing enough to buy some for their own children so they could take part in the festivities (World Cup 2010: Organisers will not ban vuvuzelas). From the perspective of a fan, the reviews are also mixed. As an owner of a vuvuzela myself, I promote their use on the basis of novelty and adrenaline-fueled fandom. However, Matt Snelling doesn’t share the same perspective. He offered an interesting take on the horns’ use in 2010 by stating, “Because the noise continues at the same level, seemingly unconnected to what’s going on down on the pitch, you don’t get the fantastic, organic crowd noises, as one group of fans cheers whilst the others suffers … Instead it’s a constant monotone sound, that for me anyway, takes you out of the action rather than immersing you in it” (Platt). As a consequence of their mixed popularity and the long-term hearing loss associated with the instrument, they were banned from subsequent competitions. Some of the major implications include bans from the Champions League, Europa League, and Euro Cup (Holt).

The second major source of debate was the Jabulani ball used during the 2010 World Cup. The word “Jabulani” means “to celebrate” in Zulu. However, its implementation in World Cup matches sparked anything but celebration in 2010 (Warshaw). As James Platt put it, “Each time the “vuvuzela din dies down, we move on to the Jabulani ball – how it’s ruining the tournament, how goalkeepers hate it, how players hate it, how it’s possibly even less popular than those plastic horns.” FIFA claimed to have run successful preliminary tests and Adidas, the maker of the ball, blamed altitude rather than design for the odd movement of its product. Goalkeepers say it is hard to handle and receive, and star players say that it is impossible to pass, cross or shoot with much control (though Diego Forlan probably disagrees with this statement). However, at a certain point, the ball was released at a time where all players had sufficient time to get used to it. Even if you don’t respect that argument, you must concede that since everyone is using the same ball, the playing field remains fairly even. England coach Fabio Capello was one of the most outspoken individuals during the 2010 World Cup, citing that the Jabulani is the “worst ball he has ever seen” (World Cup 2010: Fabio Capello). Its odd flight after hitting the foot of Clint Dempsey may have even cost the English a victory against the US after their keeper, Robert Green, mishandled the shot and allowed the ball to penetrate the net. However, there was a case of someone who seemed to enjoy using the ball. A player who flourished under and earned the limelight in 2010 was Uruguayan Diego Forlan. “[He] was a man with golden hair, with a very athletic body capable of doing extraordinary things with the ball” (Shafquat). His ability to control the trajectory of the ball was immortalized in each of his five goals. Had he scored a sixth, he may have lifted his nation to a 3rd place finish over football powerhouse Germany.

Looking forward to the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, there are two new game accessories to keep in mind – the caxirola and the Brazuca. The caxirola is a pear-shaped plastic percussion piece has become the musical instrument choice for the 2014 FIFA World Cup after being approved by the Brazilian Ministry of Sport (Holt).

It is interesting to note that the inventor of the caxirola is Brazilian composer Carlinhos Brown, who was nominated for an Oscar in 2012. In the way that a vuvuzela resembles a swarming pack of bees, the caxirola resembles a caxixi, a “woven Indian instrument filled with dried beans.” The instrument will be used in order to “create a unique Brazilian atmosphere in the stadiums” (Abdessadok). Brazilians are hoping that the newly approved instrument does not completely follow the same path as the vuvuzela; rather, they’d like to see its lifespan last much longer than the recently banned South African trumpet. The unofficial dress rehearsal for the caxirola was supposed to be the Confederations Cup this past summer, but it was banned from the competition at the end of May (Xinhua). The reason for the ban rests on previous incidents where fans hurled hundreds of noisemakers onto the pitch and caused a significant stoppage of play in order to clean the mess up. Hopefully that ban doesn’t hinder the emergence of the Brazilian noisemaker onto the world stage in anticipation of the largest human spectacle to date.

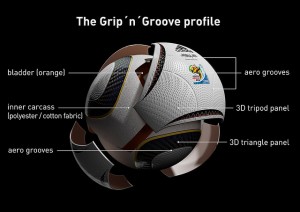

The final point of interest I’d like to mention for the 2014 FIFA World Cup is the new ball that Adidas designed – the Brazuca. The ball consists of “six interlocking symmetrical panels, made of a polyurethane casing material, surrounding a latex bladder” (Scott). The design is made so that the number of seams on the ball allows for a truer trajectory, a characteristic that many claim the Jabulani failed to exhibit. It will certainly be interesting to see how players perceive this ball and if it will lead to as many controversies as its predecessor did in 2010.

This post formerly ended questioning the performance and reception of both the Brazuca and the caxirola in the 2014 World Cup.

In 2013 FIFA and Adidas extended their partnership to 2030 a partnership which includes various joint ventures and projects, including Adidas supplying Goal balls to football programs throughout the world which are in their infancy through FIFA Goal, providing personnel and equipment for seminars and workshops, and designing the FIFA World Cup game ball. The Brazuca served as the official 2014 FIFA World Cup Match Ball. Reviews from players and bloggers alike were rather generous and optimistic about the potential of the ball. Adidas applauds the Brazuca for” the stickiness factor of the name, its perfect body ensuring performance and control.” The Brazuca is the result of more than three years of development and consultation “[and] the testing involved 600 players, including goalkeepers, defenders, midfielders and strikers to make sure that it works for all positions of the game. Furthermore, 280 players were interviewed, of which 30% were non-adidas contracted – because independent and honest feedback is absolutely key when you are striving for perfection.” Check out the diagram below for more information.

Players Iker Casillas and Dani Alves have commented that: “The Brazuca has a stunning design that feels inspired by Brazil now the ball has been launched, the tournament feels a lot closer. I’m looking forward to playing in Brazil with a great ball.” and “My first impression of the brazuca is of a ball that is fantastic, and we’re going to have a lot of fun with it. adidas has created an incredible-looking ball fitting for a tournament as big as the FIFA World Cup. Most importantly, it plays well on the ground and in the air. I’m sure all the players will love it! It’s increased my levels of excitement even further and I honestly can’t wait for the opening game”, respectively. Iker Casillas referred to the Jabulani, the 2010 FIFA Match Ball, as rotten.

Check out the official Brazuca commercial—> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PImQsVsXCr

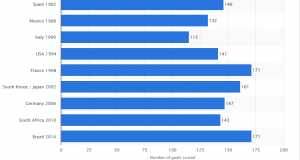

The Brazuca also has been credited with saving goals at the World Cup. As the graph below indicates, before 2014 170+ had not been scored since the 1998 World Cup in Sweden.

The caxirola, on the other hand, was not so warmly embraced–one journalist even commented that the Brazilian Ministry of Sport would have been better off passing out valium. (See the picture below for a view of the caxirola) Although not as impactful as the Match Ball, the World Cup instrument still is significant in contributing to morale and overall atmosphere.

Works Cited

Abdessadok, Zineb. “Caxirolas: The Vuvuzelas of the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil Read more: Caxirolas: The Vuvuzelas of the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil | TIME.com http://newsfeed.time.com/2013/04/29/caxirolas-the-vuvuzelas-of-the-2014-fifa-world-cup-in-brazil/

“Brazuca” <http://www.fifa.com/worldcup/organisation/match-ball.html>

“Brazuca- An Icon is Born” Adidas Group Magazine <http://www.adidas-group.com/en/magazine/stories/product/brazuca-icon-born/>

Crace, John. “Caxirola Spare us the sound of the 2014 World Cup” The Guardian. 25th April 2013. <http://www.theguardian.com/football/shortcuts/2013/apr/25/caxirola-2014-brazil-world-cup

Holt, Sarah. “Brazil unveils shaky answer to the vuvuzela for World Cup.” CNN. Cable News Network. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc., 24 Jul 2013. Web. 3 Dec 2013. <http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/29/sport/football/caxirola-brazil-world-cup-2014-vuvuzela/>.

Platt, James. “The Big World Cup Debate – Vuvuzelas and the Jabulani Ball.” Collins Beans. Blogspot, 18 Jun 2010. Web. 3 Dec. 2013. <http://collinsbeans.blogspot.com/2010/06/big-world-cup-debate-vuvuzelas-and.html>.

Reddy, Luke. “World Cup 2014: GLT, vanishing spray, Caxirola and Brazuca”. BBC Sport, 12th June 2014. <http://www.bbc.com/sport/0/football/27769533>

Scott, Nate. “Adidas unveils Brazuca ball for World Cup in Brazil.” USA Today. Gannett Company, Inc., 3 December 2013. Web. 3 Dec 2013. <http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/soccer/worldcup/2013/12/03/brazuca-adidas-ball-world-cup-brazil/3863793/>.

Shafquat, Syed. “Forlan masters Jabulani.” The Daily Star. Daily Star, 12 Jul 2010. Web. 3 Dec 2013. <http://archive.thedailystar.net/newDesign/news-details.php?nid=146409>.

“Total number of goals scored at each FIFA World Cup from 1930 to 2014” The Statistics Portal. <http://www.statista.com/statistics/269029/number-of-goals-scored-at-fifa-world-cups-since-1930/>

Warshaw, Andrew. “A ball by any other name….” ESPN FC. ESPN Internet Ventures, 16 Jun 2010. Web. 3 Dec 2013. <http://espnfc.com/world-cup/columns/story?id=797636&cc=5901&ver=us>.

“World Cup 2010: Fabio Capello slams ‘worst ever ball’.” BBC Sport. BBC, 16 Jun 2010. Web. 3 Dec 2013. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/football/world_cup_2010/8743207.stm>.

“World Cup 2010: Organisers will not ban vuvuzelas.” BBC Sport. BBC, 14 Jun 2010. Web. 3 Dec 2013. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/football/world_cup_2010/8737455.stm>.

Wyatt, Ben. “History of the vuvuzela: The fight for the right to the horn.” CNN. Cable News Network. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc., 17 Jun 2010. Web. 3 Dec 2013. <http://www.cnn.com/2010/SPORT/football/06/17/world.cup.vuvuzela.africa/>.

Xinhua. “Brazil bans caxirola at Confederations Cup.” Global Times: Discover China, Discover the World. Global Times, 28 May 2013. Web. 3 Dec 2013. <http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/784855.shtml>.

How to cite this article: “Vuvuzela, Jabulani, Caxirola, & Brazuca!,” Written by Ramsey Al-Khalil (2013), Soccer Politics Pages, Soccer Politics Blog, Duke University, http://sites.duke.edu/wcwp (accessed on (date)). – See more at: http://sites.duke.edu/wcwp/world-cup-2014/the-2010-south-africa-world-cup-highlights-politics-lessons-for-brazil/vuvuzela-jubulani-and-caxirola-debates

This is the page I will be editing.

This is great stuff! You can read Achille and I presenting a ringing defense of the vuvuzela here: http://africasacountry.com/the-vuvuzela/