The Back Room

Written in 2009 by Jeff Nash.

Edited and Updated in 2013 by Christopher Nam, Sanket Prabhu, and Jarrett Link.

***

“Some people believe football is a matter of life and death, I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.” –Bill Shankly

The interesting thing about football is that it very rarely can subsist independently from its surroundings. All-inclusive, it is the game of the rich and the poor, the black and the white; football is the democratic game of the people. From the very grassroots level to the top echelons of international competition, football invites participation from new players and continuing interest from spectators, and there exists an inert power within the sport to captivate and manipulate nearly everything nearby. Although it is a characteristic of sports in general to amass public engagement, football’s dominating world presence grants an unprecedented stage for worldwide influence, money exchange, and political agenda advancement. Due to the sheer popularity of the world’s game, lives have been lost, riches have been amassed, and countless political strategies have been allowed to fornicate and flourish with the simple association of a name on a scarf. Football has been the enabling tool for players, owners, and politicians to seek fame and fortune, and with no other leisurely activity in the world can such meaningful interspersions of sport and culture be found.

A recent visitor to Duke University was former Juventus, Parma, Barcelona and France star Ruddy Lilian Thuram-Ulien. Named to Pelé’s Top 125 Players of All Time1, Thuram gained massive stardom through his escapades on the pitch, winning numerous trophies around Europe and the world. Included in his impressive resumé on the pitch is a FIFA World Cup triumph in 1998 and runner-up trophy in 2006, a UEFA European Football Championship in 2000, a FIFA Confederations Cup victory in 2003, and that is only at the international level. He has achieved similar accolades playing club football in France, Italy, and Spain, having won the Coupe de France in 1991, the Italian Cup in 1999, the Italian Super Cup three times in 1999, 2002, and 2003, the Serie A scudetto in 2002 and 2003, and the Spanish Super Cup in 2006. In 1997, Thuram was also named French Footballer of the Year by the FFF2, a very honorable distinction. Perhaps his career-defining moment came in the 1998 World Cup semi-finals when he scored two international goals against Croatia to send France into the final with a 2-1 victory. An easily-recognizable international figure, Thuram’s illustrious career came to a premature end in 2008 when a cardiac problem, similar to the one which claimed the life of his brother, was discovered.

Thuram’s lasting importance to the world does not end, however, with him hanging up his boots. Playing off his widespread public recognition, Thuram has sought the media limelight in order to further his personal fights against racism and promote the philanthropy of his private organization, the Lilian Thuram foundation. Due to his upbringing in the southern outskirts of Paris in an immigrant family—a place traditionally fraught with ethnic violence—Thuram has the vantage point of having been a person who understands and has lived with racism his entire life with a view at the very source. “Violence never happens for no reason,” says Thuram. “You have to understand where the malaise comes from. Before talking about law and order, you have to talk about social justice.” 3 Indeed, social justice as well as equality among all races, genders, and social classes is exactly the cause Thuram holds most dearly.

Since his career’s end, the well-read Thuram has toured all over the world spreading his message of colorblind acceptance. “I am not black,” he points out, preferring to refer to himself as either French or a member of the human species. 4 As racism pertains to the beautiful game itself, Thuram has been famously outspoken, especially with regard to France and Italy, where racist chants routinely go lightly punished. Says Thuram, “If there is a young black person in the stadium or at home watching on TV, he will feel small if he hears the monkey chants. If the fine is insignificant, the black fan may have a sense of being a victim and may become racist towards white people. Some white people in the stadium get the message that it is not serious. The authorities have to make an example of those guilty of racism and punish them hard. Taking points away would show the authorities were serious.” 5 He intends to continue touring different areas of the world, hoping to one day reverse discrimination against all peoples, and through his international respect for his beauty on the pitch, it is possible that his beauty through words will carry more meaning for many.

Football is not only an opportunity for players to advance their personal agendas, but also a way for a core group of individuals to attempt to make large sums of money. In a game where the most valuable clubs sport a total worth of nearly two billion dollars 6, and the highest-paid players net more than 13 million dollars per year 7 (excluding bonuses and endorsements, another enormous contributor to salary), it is clear that the financial muscle behind the highest level of the game is extremely powerful. With astronomical intakes from television revenue, competition rewards, and merchandise sales, to be a stockholder in one of the top clubs in the world virtually guarantees a personal fortune in the long run. Such is the perceived low-risk investment of such business tycoons as Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Abu Dabhian owner of Manchester City with a family net worth approaching $1 trillion 8, or American entrepreneur Malcolm Glazer, chairman of Manchester United. Although sometimes the politics between owners and fans is turbulent, the inclusion of high-profile figures at the helms of the economics of the game signals the importance those in charge may carry. The need for financial success represents a double-edged sword, a constant struggle between a stage to further superstardom and a crushing arena for public criticism.

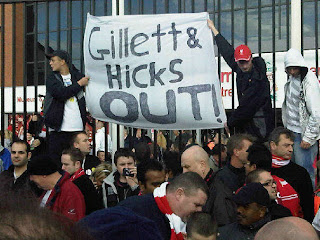

When American business duo Tom Hicks and George Gillett assumed control of renowned English side Liverpool FC in 2007 from longtime chairman David Moores, their introduction to the backroom of one of the most famous clubs in the world was met with bright, yet cautious optimism. At a time when Liverpool’s fortunes seemed to be on the downturn—they were being consistently outspent by Premiership rivals Manchester United and Chelsea in their attempts to capture new talent, and they hadn’t won an English league title since 1990—many fans initially viewed the new ownership as a welcome financial opportunity to bring the squad to par. In addition, financial success from Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium and Manchester City’s City of Manchester Stadium were beginning to show legendary Anfield’s weakness; with around 45,000 seats, the club was operating with a debilitating lack of ticket revenue. However, as events unfolded and perceived promises from the owners were left unfulfilled, Hicks and Gillett were made to witness the power of organized fan base action as high-profile criticism and demonstrations spread rapidly. 9

The preparations for the highly-publicized stadium in Stanley Park to date have been effectively meaningless; ground has not yet been broken for the new grounds, and calls for the American owners’ resignations are widespread. The owners have breached their supporters’ trust in failure to back manager Rafael Benítez in the transfer market, an expensive refinancing arrangement has resulted in the stadium construction being delayed indefinitely, and the club’s recent ill fortune on the pitch has increased pressure around the club immensely. The voices of Liverpool supporters are fervently in opposition to the owners’ continued leadership, and arrangements for marches and protests against the Americans are prevalent and pervasive in Liverpool and even before (and during) games.

Gillett and Hicks, recently resigned in the press to ending their joint ownership with at least Gillett aiming to leave the club, are representative of those in money and their touchy relationship with the game. Failure to bring in talent such as Gareth Barry last season after having publicly announced that “[i]f Rafa said he wanted to buy Snoogy Doogy, [they] would back him” 10, and the continuing economic struggles of the club raises the question of whether sport and finances can ever truly mix. Fans control the monetary intake of the club, and fans are intent on seeing their club succeed. Therefore, in order to have an owner enjoy the full backing of the supporters, money will need to be spent from their own coffers to ensure short and long-term success on the pitch. Businessmen, however, are by their very nature concerned with their own profit, and private spending is therefore rare at best. With these two mixtures in ideologies, a common ground is very difficult to find.

The best personification of politics and football intermingling is the Italian Serie A. Based on a long and extensive story of success, passion, and behind-the-scenes meandering, Italian soccer’s history has been fraught with scandal and corruption, a dark characteristic which has both affected and been influenced by football’s all-encompassing grip. This combination of traits both positive and negative, both inventive and exploitive, both political and recreational can best be symbolized through notorious Italian Prime Minister—and AC Milan owner—Silvio Berlusconi.

When Silvio Berlusconi gained ownership of AC Milan in 1986, he assumed control of one of the defining success stories in Italian football history. Founded in 1899, the Milanese club has amassed an impressive 17 league titles, 18 officially recognized international titles, and 7 European Champions League honors and has been home to such stars as Ronaldinho and Frank Riijkard. 11Charismatic, controversial, and inspired, Berlusconi is one of the most colorful, yet important figures in modern Italy. The first time he won election as Italian Prime Minister in 2001, he triumphed in spite of heavily-detailed allegations from British magazine The Economist detailing alleged “tax fraud, false accounting and links with the Mafia 12,” a foreshadowing of the many legal battles Berlusconi would fight throughout his three terms. However, due to a mixture of judicial policy, circumstantial evidence, and an ability to afford capable lawyers, Berlusconi has escaped imprisonment. Berlusconi himself has always attributed the allegations as being related to political gain, maintaining that they were “judicial persecution, which I am proud to resist 13.”

This sense of corruption in Italy and Italian politics has long been widespread and is indeed ingrained within football and society itself. The presence of indignity is not exclusive to the Prime Minister or the government, and football in Italy has been characterized in the past by several notable scandals and a similar overriding sensation of corruption. In 1927, due to a bribing scandal in which Torino paid a defender for city rivals Juventus to underperform in a game matching the two teams, which Torino won 2-1, Torino was stripped of their league title. In 1980, a match fixing fiasco was unearthed which resulted in AC Milan and Lazio being relegated and Milan legend Paolo Rossi receiving a ban. Juventus club doctor Riccardo Agricola was convicted of doping players in the mid 1990s, and in 2005, Genoa’s successful Serie B promotion campaign became a relegation to C1 after it was discovered that the club bribed Venezia to guarantee a victory in the final game of the season18. It was of no surprise, then, when in 2006 a major match-fixing scandal again arose, with Berlusconi’s AC Milan, Lazio, Reggina, Fiorentina, and Juventus all facing punishment. Juventus were punished most harshly after accusations of “criminal conspiracy and sports fraud” were verified by an investigative panel, and although all the clubs faced fines and point-deductions, champions Juventus was relegated to Serie B 14. The highly-organized and syndicated debacle stunned the soccer world, and a wide array of resignations and bans surfaced, and although the Italian people were mortified, they were largely unsurprised by the news. The prosecutor of the case, Antonio Di Pietro, noted that “at the time of [his] inquiry everyone said, ‘But it was known corruption was widespread 15.’” This well-established presence of foul play seems to exemplify the ideological similarities between backdoor politics in the country and its simultaneous existence in the country’s most popular sport.

The most remarkable characteristic of the world’s game is that in a certain sense, the good and bad elements of outside influences and inert opportunities for personal game only add to the prestige of the sport. The ability of football to be able to encompass a capacity for human rights activism, entrepreneurship, and political significance demonstrates the importance 22 men and a ball can have on society. Nowhere else in world civilization can a singular event have such ramifications on culture, and the notion that such important commodities as government and economics are directly influencing and influenced by football demonstrates better than anything the power of this game. Some have argued that football is a religion, others that it’s a frenzy; I might argue that it’s an extension of society itself. But what is the significance? People have dedicated their lives, and in some cases lost them, for football. Others rely heavily on its influence for inert self-meaning. It is a platform for change, both personal and worldwide. And that in and of itself contains ramifications which may alter the very framework of global social order.

Return Back to Media/Markets/Football in Contemporary Europe

How to cite this article: Jeffrey Nash (2009), Christopher Nam, Sanket Prabhu, and Jarrett Link (2013), “The Back Room,” Soccer Politics Pages, http://sites.duke.edu/wcwp/research-projects/mediamarketsfootball-in-contemporary-europe/the-back-room/

Image sources left as hyperlinks on respective images.

- “Lilian Thuram’s off-the-pitch courage.” ESPN. 26 Feb. 2009. See http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/blackhistory2009/columns/story?columnist=lapchick_richard&id=3934455 ↩

- THURAM profile from FootballDatabase.com. See http://www.footballdatabase.com/index.php?page=player&Id=215&b=true&pn=Ruddy_Lilian_Thuram-Ulien ↩

- “Soccer heroes blame social injustice.” The Times Online. 10 Nov 2005. See http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article588473.ece ↩

- See #3 ↩

- See #3 ↩

- Soccer Team Valuations. Forbes. See http://www.forbes.com/lists/2009/34/soccer-values-09_Soccer-Team-Valuations_Rank.html ↩

- Highest Paid Footballers 2008/2009. Ian Sims. See http://www.iansims.com/football/highest-paid-footballers-20082009/ ↩

- “Trillion-dollar wealth of new Manchester City owner Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan.” Mirror Football. 03 Sept 2005. See http://www.mirrorfootball.co.uk/news/Trillion-dollar-wealth-of-new-Manchester-City-owner-Sheikh-Mansour-bin-Zayed-Al-Nahyan-article38353.html ↩

- “Hicks & Gillett love the green of the dollar more than the red of Liverpool FC.” This is Anfield. 02 Nov 2009. See http://www.thisisanfield.com/2009/11/02/hicks-gillett-love-the-green-of-the-dollar-more-than-the-red-of-liverpool-fc/ ↩

- See #9 ↩

- A.C. Milan – Club History. See http://www.acmilan.com/InfoPage.aspx?id=452 ↩

- James Newell, The Italian General Election of 2001: Berlusconi’s Victory (New York: Manchester UP, 2002), 1. ↩

- “Judges urged to jail Berlusconi.” BBC News, November 12, 2004. See http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4007441.stm ↩

- Previous Italian football scandals. See http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/print?id=2492260&type=story ↩

- John Hooper, “Serie accusations.” The Guardian Online, May 12, 2006. See http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2006/may/12/worlddispatch.italy ↩