Written in 2009 by Sara Murphy and Alex Tschumi

Edited and Updated in 2013 by Kavin Tamizhmani, Becca Fisher, Caitlin Moyles, Rosa Toledo, and Elena Kim

A significant part of Zinedine Zidane’s global popularity stems from the widespread dissemination of his image. Like Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, and David Beckham, among others, Zidane has exploited his identity as an athletic icon to garner economic profit. Furthermore, he has utilized his branding as a symbol of success in multiracial integration in order to appeal to broad commercial audiences. From a business standpoint, this capitalization has been a calculated and tactically implemented strategy. Unlike several of his teammates on the French national team, Zidane has chosen to avoid controversy, especially when speaking about social and racial issues. In a country like France, where social and racial unrest seems to punctuate news programming on a nightly basis, there is an inherent commercial value attached to a seemingly “uncontroversial” advertising figure. Rather than harnessing his image as an integrated Frenchman of Kabyle ancestry to provoke social commentary, Zidane has used it to further his commercial interests.

When signing sponsorship arrangements, firms aim to expand brand awareness and strengthen brand image.[15]Companies will often disseminate their advertisements utilizing many forms of promotional media with the goal of reaching as many consumers as possible. The consumer constructs brand associations upon seeing advertising, and in turn identifies the athlete’s image with a product. In many ways, the celebrity’s image is fully reassigned to the brand.[16] Paralleling the use of celebrity images, brands will often sponsor events to create links between certain popular competitions and their products. In the 1998 World Cup, the sponsorship opportunities were boundless, offering companies a wide range of matches, geographic targets, and a diverse set of players with different images to choose from in order to manipulate the kind of associations consumers made about their brands.

While the 1998 World Cup was obviously a competitive football tournament, it has also been identified and analyzed as an advertising competition between multinational firms. Ironically, its organizing body, FIFA, determined that the area reserved for the emblems of both sponsors and the football federations should be the same, highlighting the importance of economics in football.[17] Perhaps the most publicized battle occurred between Nike and Adidas, the two most prominent producers of football apparel in the world. The culmination of both the football and advertising competitions was the final match, played between France (whose sponsor was Adidas) and Brazil (whose sponsor was Nike). Allegations even emerged that the two firms had influenced both national teams’ composition and strategy. While the chairman of Adidas allegedly inspired the omission of the international stars Ibrahim Bâ and Eric Cantona (sponsored by Puma and Nike, respectively) from competition, Nike was accused of forcing Ronaldo, its “marketing poster boy,” to play in the championship game despite a convulsive fit and seizure suffered the night before the match.[18] This commercial presence reinforces a rather significant conspiracy theory that the World Cup and FIFA place economic interests above the founding principles of the international competition.

A common practice in World Cup marketing is to focus on a few key individuals, using carefully honed artistic tools to portray them in an arresting and almost mythical light. Zidane’s racial history and uncontroversial political stances, as well as his striking facial features, helped in this mythopoesis, making him appear as an ideal spokesperson for France as well as international football.[19] Rather than speaking about race and discrimination in France, Zidane tends to redirect conversation to his retreat from La Castellane, the Algerian immigrant suburb of Marseille, and the clear-cut morals he learned from his family.[20] His story perpetuates the image of the multiracial and successfully integrated Frenchman, almost as if paralleling a folk tale. Using this constructed image, Zidane established his commercial niche in a 1998 Adidas advertising campaign that profiled racially and ethnically diverse players on the French national team alongside white players. The subliminal use of race in black and white photographs and television advertisements aestheticized the diversity of the French national team, and profited from France’s insistent need for reassurance about its racial and ethnic tolerance. Similar strategies were employed in the victory celebration on the Champs Elysées, where Zidane’s face was projected onto the facade of the Arc de Triomphe, as if an icon of a “new France”, and the Algerian flag fluttered alongside the French tricolore, as if consigning the long, bloody, painful battle over France’s former colonial possession to oblivion.

Zidane’s commercialization and financial success can be attributed to and analyzed within a series of conscious and strategic career decisions. By leaving Bordeaux in 1996 to play at Juventus, he enabled his brand to expand to a more profitable market niche and provoked comparisons to France’s last iconic #10, Michel Platini. By moving to Italy, Zidane also entered a different football economy. At the time, the best-paid French players in Italy could make up to 30 million French francs per year, while those who remained in France earned only about a third of that sum.[21] After establishing himself as a pre-eminent attacking midfielder in Europe and winning a World Cup, he parlayed this success into a move to Real Madrid for 77 million Euros, which was at the time the most expensive transfer fee in history. From 2001 to 2006 he played with the “Galacticos,” the most famous and powerful squad in the world, utilizing international competitions and world publicity tours to promote and expand his advertising viability. Indeed, by 2006 his receipts from advertising contracts—some 8.6 million Euros—almost doubled his 6.4 million Euro player’s salary from Real Madrid.[22]

Zidane’s global recognition and power within the football world allowed him to dictate the terms of his sponsorship deals as well as the dissemination of his carefully guarded image. He once stated, “Je ne serai jamais récupéré si je ne le veux pas,” refusing to be defined or exploited by any political or commercial cause without his explicit approval.[23] In fact, it is reported that his agent, Alain Migliaccio, automatically refuses any business proposition that guarantees Zidane less than one million Euros[24]. Based on his standards of dignity, Zidane once rejected an endorsement deal that would have placed his likeness on shopping bags, contending that shopping bags inevitably end up on the floor and that his image should never be so defaced or degraded.[25] This cautious management of sponsorship opportunities allows Zidane both to retain his dignity and to spread his brand through companies that have included Adidas, the food group Danone, the communications giant France Telecom, and the insurer Generali France, among others.[26]

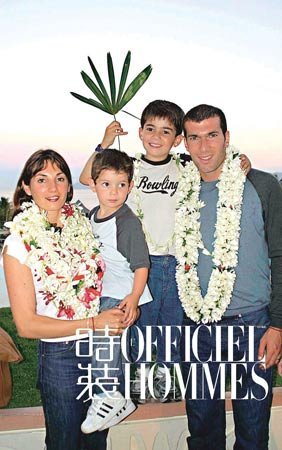

Zidane has often been compared to Michel Platini, who played a similar role for Juventus in the 1980s. However, unlike Platini, Zidane generally opted out of the media scrutiny and playboy image cultivated by other stars of his generation. While many footballers become tabloid cover fixations, Zidane’s private life has always been withheld. Indeed, Zidane’s intense privacy and inherent shyness, often described as verging on social clumsiness,[27] are not infrequently cited among the reasons for his refusal of a more coordinated political use of his image, as adopted by 1998 teammates such as Lilian Thuram.[28] Zidane does not allow himself to be caught in situations that affect his public image, instead choosing to display himself as an attentive and responsible family man. For example, during the month following the 1998 World Cup final, he was photographed for the cover of Paris Match, a prominent French weekly magazine. Rather than pictured on a field kicking a football or in a locker room preparing for a match, Zidane was instead shown posing with his wife and young sons on the beach. This careful marketing on the part of Zidane and his publicists propagates an image of Zidane as a family man, which acts as both a national and transnational sales pitch. The depiction of a Frenchman with immigrant roots as harmless and “domesticated,” with strong familial ties, goes against many of the racial stereotypes proliferated in France, contributing to the sellable Zidane success story. Thus, in creating a public persona whose priorities, as Andrew Hussey has noted, are “football, family, and friends,” Zidane has engineered an “appeal [that] transcends the religious and racial divide in one of the most tense multi-ethnic societies in Europe.”[29]

In eschewing the direct expression of political positions and guarding his privacy, Zidane has become a public figure who is both extremely popular and “resolutely unknowable” to the majority of the French public.”[30] This enigmatic status may be in part responsible for his magnetic power as a public relations and marketing icon. However, a key role in the success of Zidane’s brand has been his careful construction of his image of bedrock communal values that are widely shared and easily comprehended by the French public: responsibility (note teammate Thierry Henry’s much-quoted description of his teammate as “the guy we can always count on, the one who really takes control”), hard work, talent, determination, and fidelity to the family and friends who have stood by him in his meteoric transformation. While the lens of this website is confined to the role of the 1998 World Cup victory on Zidane’s image, it bears repeating that Zidane’s presentation of himself as a private and moral family man was altered by his head-butt in the 2006 World Cup Final and that the mystery surrounding Zidane’s action became an obsession for many football fans. Nonetheless, Zidane’s popularity in France was not significantly affected by the action, and many argue that his response to Marco Materazzi’s taunts was, in fact, moral. Marie-Christine Lanne, the marketing head of Generali France, has explained his commercial value and appeal, stating that “Zidane est déjà entré dans l’histoire. Son image est très forte en dehors du terrain. Il inspire la confiance et représente la compétence, le talent, avec, en plus, une élégance morale” (italics mine). [31] Zidane’s insistence on these fundamental values underscores his broad appeal and consequent marketing success. However, the nonpolitical force of this approach is accentuated by a singular fact in Zidane’s history: the removal of a significant quote from the second edition of the book Mes copains d’abord that he published with teammate Christophe Dugarry after the 1998 World Cup, despite his frequent affirmations of his proud Algerian origins and Kabyle identity. In the republished version, Zidane’s explanation of the ethnic power of the victory (“It was for all Algerians who are proud of their flag, who have made sacrifices for their family but who have never abandoned their own culture”) is nowhere present, having perhaps been judged too specific, “political,” or divisive for a general-audience market.

Zidane’s iconic power has been put to use in broad humanitarian campaigns in the wake of the 1998 World Cup. Key among them is his collaboration with Ronaldo on the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) campaign “Teams to End Poverty” in late 1999, as well as his appointment as a UNDP Goodwill Ambassador in March 2001.[32] As part of a broad-based, non-partisan effort to engage support for reducing poverty throughout the developing world, Zidane and Ronaldo appeared in an advertising campaign photographed by noted fashion photographer Dominique Issermann that was issued on a pro-bono basis in more than 150 media outlets in Europe. The press release for his appointment as a Goodwill Ambassador observes Zidane’s prior involvement “in a number of social and humanitarian actions mostly in a private manner,” singling out appearances in charity football matches to benefit SOS Children Villages and Secours Populaire Francais in early and late 2000.[33] While Zidane has engaged in private efforts in Algeria and in the Marseilles suburbs, the majority of his publicized work as a spokesperson on behalf of education, children’s services, and poverty reduction—much like his commercial enterprise—is nonpolitical in nature.

As Zidane has carefully regulated his image to increase commercial appeal and minimize controversy, questions have emerged about the kind of impact he might have had on a racially unstable nation like France had he been more willing to develop his image as a more forthright political symbol. These hypotheses are supplemented by arguments that racial and socioeconomic harmony in France has waned, rather than increased, since the initial acceptance of France as a multiracial nation following the 1998 World Cup victory. While Zidane’s public persona has allowed him to accumulate wealth and to publicize different charitable causes, it has done little to affect the way minority populations are treated or perceived in French politics. Had Zidane utilized his celebrity politically, he could arguably have lessened racial tensions, or at least broadened understanding of present-day immigrant communities. Indeed, newspaper editors, journalists, and concerned citizens have often asked themselves in the aftermath of the 2002 run-off election between Jacques Chirac of the conservative UMP and Jean-Marie Le Pen of the xenophobic National Front: What became of the joyous, unified, multi-ethnic France of the 1998 World cup victory celebration? Would Zidane’s cultivation and use of his image as an ethnic minority have facilitated a more “unified” and enduring result?

Since his retirement after the 2006 FIFA World Cup, Zidane has continued to appear in ad campaigns for Adidas in addition to other brands including Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior. In fact, Zidane was Christian Dior’s first male model, according to Forbes Magazine, which speaks to his striking features and magnetism as an object of desire.

Louis Vuitton’s 2010 “Core Values” ad campaign brought three of the all-time greatest football players—Maradona, Pelé, and Zidane—together for a game of table soccer.

How to cite this article: “The Commercialization of Zidane’s Image After 1998,” Written by Sara Murphy and Alex Tschumi (2009), Edited and Updated by Kavin Tamizhmani, Becca Fisher, Caitlin Moyles, Rosa Toledo, and Elena Kim (2013), Soccer Politics Pages, Soccer Politics Blog, Duke University, http://sites.duke.edu/wcwp (accessed on 10/17/13).

________________________________________________________________________________________________

[15] Gwinner, K., and Eaton, J. “Building Brand Image through Event Sponsorship: The Role of Image Transfer.” Journal of Advertising 28.4 (1999): 47.

[16] Ibid., 48.

[17] Silverstein, P. “Sporting Faith: Islam, Soccer, and the French Nation-State.” Social Text 18.4 (2000): 39.

[18] Ibid., 39.

[19] Kaelin, L. “Explaining Zidane: A Deconstruction with Adorno and Derrida.” Loyola Schools Review 6 (2007): 124.

[20] Vinocur, J. “Just a Soccer Star, After All.” New York Times 14 Mar. 1999: SM32.

[21] Mignon, P. “French Football after the 1998 World Cup: The State and the Modernity of Football.” Sport in Society 2.3 (1999): 232.

[22] “Sponsors Stick with Zidane Despite Head-butt.” USA Today. 11 Jul. 2006.

[23] Dauncey, H., and Morrey, D. “Quiet Contradictions of Celebrity: Zinedine Zidane, Image, Sound, Silence and Fury.”International Journal of Cultural Studies 11.3 (2008): 301-20.

[24] Miquel, P., Stehli, J.-S., and Vidalie, A. “Icône malgré lui.” L’Express 8 June 2006.

[25] Dubois, Soccer Empire, 257.

[27] Silverstein, “Sporting Faith: Islam, Soccer, and the French Nation-State,” 41.

[28] Mbembe, A. “To Defend and to Question.” Chimurenga 10 (2006): 235.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Miquel et al, “Icône malgré lui.”

[32] United Nations. “French Soccer Champion Zinedine Zidane to be Appointed UNDP Goodwill Ambassador.” United Nations Information Service. 7 Mar. 2001.