Beijing Through Sidney Gamble's Camera 一百年前的北京社会–西德尼·甘博摄影图片展

Movement Defining the Modern: The Role of Human Effort in Creating Modern China

By Kshama Kumar

Kshama Kumar is a PhD student at Duke University and has published on art and cinema in South Asian Popular Culture and Wide Screen Journal of Cinema Studies

Sidney Gamble travelled and captured a changing China in his various trips to the country in the early part of the twentieth century. His images provide an intriguing ingress into post-Qing Empire China and prove to be a window into everyday life in China during a time of tumultuous change. My interest is not only in the images themselves but also in our gaze as spectators. There are two interventions embedded within this narrative. The first intervention is Sidney Gamble’s visit and photography of China in the twentieth century. The second is ours, as a twenty-first-century audience. Gamble functions in various capacities during his many trips to China. As tourist, traveler, surveyor and member of the YMCA, he dons several roles at various moments. Three of Gamble’s perspectives are of concern here: Gamble’s role in the Mass Education Movement, his work as a surveyor, and his aesthetic intervention through photography. Gamble moreover was in China during some of the key moments approaching modernity. He and his camera were thus key witnesses of this change.

China was moving into a new era with rapid changes. The Qing Empire had given way to a Republic, Sun Yat Sen had emerged as a popular leader, and the mobilization of people towards a changing regime was in full swing. We can see the movement of historical time in movements for socio-political change: the rickshaw pullers strike leading to the May Fourth Movement, for example. The change from monarchy to republicanism was thus motivated by a movement and mobilization of people (Figures 2 and 4) . With changes in regime we can also see changes in systems, as for example, with the Mass Education Movement (Figure 5) or the prison system (Figure 8). At the individual level we see the physiognomy of people in motion captured through still photography and thereby frozen in time. Gamble for example, through his fascination in documenting street life, captures on celluloid rickshaw pullers and farm laborers, challenging stereotypes about “city life.” Movement consequently defined this period, be it the large institutional and structural changes sweeping the country or the effects of such changes on the individual. But how was this change manifesting itself on the environment?

The census completed in Peking by Gamble, for example, is the beginning of a modern trend towards the disappearing “individual” or human figure. People were now commutable to statistics on paper, and in practice the coming of the machine threatened to remove the human figure from the city street. Had modernization meant industrialization devoid of the human figure? Had the tram, for example, replaced a rickshaw puller in twentieth-century Beijing? The interaction between the human and his environment will be of thematic interest in this paper, as the dynamics between man and his environment change. Two ideas immediately emerge as important thematic elements endemic to our discussion of a modern China: movement and environment. Movement is organically entwined within this project through the aforementioned interventions; more importantly, movement begets change. These changes, both structural and individual, are reflected in the relationship between the human figure and his environment and therefore become central to our inquiry. These two ideas will therefore function as vanguards of this paper.

What, however, do I mean by movement? Gamble’s work is situated at the junction of a historic and aesthetic understanding of movement. Movement in Gamble’s work also functions in a dual capacity, as a historical determinant of modernity and as an aesthetic condition of modern living. Movement is both—the corporeal body caught on film and the changing China slowly pushed into “the modern.” Modernity for China was a definite move away from Confucianism and monarchy towards the appropriation of “scientific thinking” or reason. The 1920s in China was the time of many movements towards a changing society, determined on the establishment of class consciousness among the laboring classes transcending regional or local parochialism. As a result we can see the Rickshaw Pullers, Oil Press Workers, the Machinists, and the Railroad Workers union movements coming to be associated with the changing face of Chinese society. Mobilization of the masses became the priority of those in power. The privileging of the working class was historically determined and it would be actualized through a restructuring of labor and the mobilization of “bodies” for the cause. Change was the mantra, and mobilization and movement of labor became the vehicles of this change. This period was also a time of change in public welfare systems. The health, education, and prison systems were all being restructured and “modernized.” Transportation had been revolutionized by the coming of trams and trains, and all of this entailed a movement towards a different era in Chinese history. In other words, change was redefining China, in a significant way and this change is best understood in the movement of both individuals and systems. But how do we develop an aesthetic understanding of movement?

Among many artists and theorists in twentieth-century Europe who experimented with concepts of movement, time, and the human figure is the Czechoslovakian choreographer and dance theorist Rudolf Laban, who employed these concepts within his art. For Laban, “Man moves in order to satisfy a need. He aims by his movement at something valuable to him.” This value can be both spiritual and intellectual or material. He continues, “[s]o movement evidently reveals many different things…. Movement may be influenced by the environment of the mover. So, for instance, the milieu in which action takes place will color the movements of an actor or an actress.” That is, the environment shapes movement.

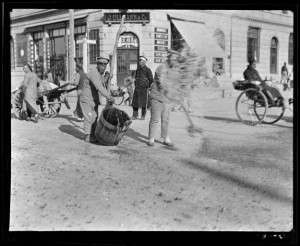

This image foregrounds a man winnowing. The movement is captured not only through his physiognomy and the positioning of his shadow but also through the leaves frozen against gravity. We see effort etched in every angle of this picture, an image that has itself been mechanically captured. The background centers on another working figure as well. More significantly we clearly see movement and effort. The effort behind his movements is aimed at securing an “object of value,” in this case the cost of living. We can observe how the environment has affected his movement. His movements are determined by his economic environment; he is perhaps a farm laborer and it is this environment that moulds the ways in which his body moves. The occupation is unequivocally etched in the folds and creases of his clothing, visible in the image. Like the movement, these folds are transitory and evoke the fleeting quality of movement. It is this embedded dynamism that points us towards the mobility of its central figure, a quality that is enhanced by the following image.

Figure 2 is of the rickshaw pullers of Beijing. Their work is movement. Their figures suggest movement and their labor is defined by movement—the movement of people and goods, the movement of the rickshaw pullers themselves, and also the movement of time, rickshaw pullers being one of the laboring classes mobilized for change. They are affected by their environment, in that their labor and effort are shaped by the demands of that economic environment. But they are also effecting change in their environment through participation in the labor movements. In Figures 1 and 2, the environment is clearly shaping the effort of the human beings, but as discussed earlier China was in a state of change. How did the environment change and what effect did it have on the human figures embedded within it?

Figure 4: Sprinkler wagon

泼水养路

562-3259

Figures 3 and 4 capture human figures in motion, seated in the rickshaws, pulling the rickshaws, but most importantly the two figures in the foreground in both images are spraying water to calm the dusty summer storms convulsing the city. The men are part of the cleanliness and hygiene drive that was itself part of a larger structural change of different systems. However, how do we read these images as an audience? Laban notes that movement is fuelled by effort and rest is the only transitory state of being, for it is effort and movement that characterize a human being. For Laban this effort is experienced by an onlooker as rhythm. Our gaze is trained not at the effort behind the movement but on the movement itself as rhythm. The experience here is not only of the person involved in the movement but also of the gaze of another human following the bodily efforts and exertions of a figure in motion. We can observe the effort intrinsic in every movement of the central human figures in both images. The rhythm of movement conveyed through not only their physiognomy but also through the spray and play of water. Moving against gravity and simultaneously frozen in space, the movement of water mirrors and is emblematic; indeed it is an extension of human movement and effort. More significantly, while the previous images explicitly showcased the ways in which the environment affected the human, Figures 3 and 4 exemplify a reversal in this process. The repartee between the figures and water highlights the ways in which man was taming and changing his environment.

These two images also underline the connections between the human figures and the change in systems, especially when compared to Figure 1. In both sets of images, we see the same form of human effort. Human economy is tied in with this effort at reorganization and restructuring. While the figure in Figure 1 is contributing his labor through the act of winnowing, he is not directly absorbed into this system of change. The two figures who are part of the hygiene drive, however, are directly connected to the structural change. The following images show even more explicitly how Gamble’s work captures the way human figures are mobilized in the name of the modernization movement.

Figures 5 and 6 capture various moments from the Mass Education Movement during the 1920s. Figures 5 and 6 depict students engaged in the movement for mass education and addresses our thoughts on mobilization of people as a characteristic feature of twentieth- century Chinese movements for change. Gamble was involved with Y.C. James Yen’s Mass Education Movement and actively documented its efforts for awareness building and mobilization. His photographs of schools and the YMCA’s mobilization drives are ample evidence of his interest in these structural changes. These images not only inform us of the structural changes ongoing in education but also transform our understanding of movement and mobilization in the twentieth century, especially when we consider the organization and composition of the bodies, the human figures. In the images from prisons, schools, and hospitals, we can see bodies being disciplined, governed, or otherwise manipulated by the systems they are embedded within. The bodies morph into uniformity and can be easily categorized, not unlike a neat column of statistics. This fact becomes visually apparent when we consider the next image.

In Figure 7 we see children being structured and organized in files and rows. The individuality of the expressions captured in this image is undercut by the homogeneity imposed through uniforms and institutionalized behavior. Gamble is a central figure not only in capturing this moment but in actualizing it through his surveys. For one of the first steps towards “modernity” is the replacement of the human figure with numbers and statistics. Once human figures fit into neat columns, the process of control and discipline can begin. This thought is more cogently examined in the images from the prisons. Consider Figure 8, for example.

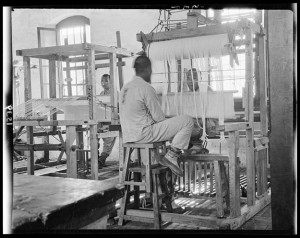

The human figures could be workers in a factory. However, the fact that it is a prison immediately transforms this space into a place reminiscent of a school. The prisoners here can be seen weaving cloth: it is a space for inclusion back into society. This fact should not be mistaken or misconstrued as the prison system belonging to the mainstream. It is a space for training and the gaining of skills, similar to a school or university. However, it vitally differs from the educational system when we consider different processes of discipline being enacted. The significant idea to engage with is the process by which bodies were being changed or transformed by the changes in structures and institutions. Schools and prisons operate of course in very different milieus of society, but they are bound together nonetheless by the changes convulsing them at the moment. Beyond the human figures and the structures in flux, the change that significantly altered the environment was the beginning of mass mechanization.

Figure 9, the coming of the first street cars to Beijing, is an image of and from a new China, a mechanized and “modern” society. Will the rickshaw pullers be replaced by a machine? Can this city space transform completely to accommodate this modern beast, and what would be the effect of such a transformation on the figure of the human? In Figure 9, the tram is figured centrally. The humans are marginalized and indeed made impersonal. Unlike the other images we are not drawn to the human figures but to this symbol of the mechanical. For Laban, movement can be voluntary or involuntary, that is without involving a conscious decision. Involuntary movements for him are especially embedded in modern societies where human beings have been subsumed by industry. Human beings become a part of the mechanical industry and their movements therefore become automatic. Individuals who are a part of the system perform movements without any conscious thought or contemplation. For Laban, movement or effort has been sapped of its vitality: the human actor. In engaging in repetitive motion, man finds himself becoming just a part of a machine and thereby growing far removed from his own energy. Mechanization bleeds the human being out of the landscape. Can we see this process unraveling in China?

Furthermore, for Laban movement was the cohesive force behind architecture, painting, and sculpture, to name a few forms, in the ancient world. Movement was central to our daily lives and the creative process. The modern condition for him is at a disjuncture with this notion, as human energy is sapped by the machines. Rhythm and movement which should have been integral parts our lives therefore become divorced from our everyday mechanical lives. Are the people truly detached in these images, and have the machines taken over this landscape? In the Chinese context, is the human architecture of the city being replaced by the industrial and the mechanized? China in reality was creating its own modernity. Modernity, at least in Laban’s European context, was replacing human movement with the mechanical. Machines were frequently employed to signal the coming of modernity but always at the expense of the human figure. China, however, is uniquely positioned as it is the human figure that shaped modernity; the mechanical could never become a stand-in for the human, as is evidenced in Gamble’s work. The tram is displacing the human, but the human still fills and indeed cannot be contained within its borders. The rickshaw puller is a fundamental part of the landscape, on the same stage as the car, or the students from the mass education movement. In the image we can see an implement, the pitchfork, but it is the human figure that is employing it gainfully. The rickshaw pullers are a dynamic part of the environment in flux. Systems are being restructured by the human hand. The human, after all was mobilizing a new China!

The human is never completely disassociated from this landscape; he finds new ways of inserting himself within this idea of the modern. Venturing further, Gamble’s work is also an act of the mechanized—the camera capturing the human. But it is the perspective, or rather view that remains inherently human. The perspective here belongs to Gamble, another human remaking the ways in which the modern Chinese landscape is remembered. The human is therefore integral not only to the context and content of the image but also the making of the image. It is therefore befitting that I conclude with an image, wrought by the human hand but ultimately a mechanical reproduction. The image taken by Gamble coalesces in a single frame some of the key concepts of human movement and mobility as captured by a camera. The image taken from what appears to be a train, frames another form of transportation, a boat. It perfectly ensconces the dual conditions of a uniquely Chinese modernity: the human and the mechanized. The train reminds us of a machine cutting through the landscape, while the man on the boat fuelling the boat’s movement with his own effort aligns himself on the other end of the spectrum. Both are immediately set up in contrast while also distinctively combining to perform what I’ve come to define as the Chinese Modern.

[i] For more read: Tsin, Michael Tsang-Woon. Nation, Governance, and Modernity in China : Canton, 1900-1927. Studies of the East Asian Institute, Columbia University. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1999. And, Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China. 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999.

[ii] For more read: Laban, Rudolf von, and F. C. Lawrence. Effort. London,: Macdonald & Evans, 1947. And, Laban, Rudolf von, and Lisa Ullmann. The Mastery of Movement. 3rd ed. Boston,: Plays, 1971.

[iii] Laban, Rudolf von, and F. C. Lawrence. Effort. London,: Macdonald & Evans, 1947.p.5.

[iv] Ibid, p.8.

[v] Ibid, p.12.

[vi], Laban, Rudolf von, and Lisa Ullmann. The Mastery of Movement. 3rd ed. Boston,: Plays, 1971.p. 2

[vii] Ibid, p. 5.

定义现代的运动:创造现代中国的人的力效

是杜克大学历史系博士生

西德尼·甘博在他二十世纪早期的多次游历中捕捉到了一个变化中的中国。他的照片为走进晚清帝国提供了十分吸引人的途径,也被公认为是一扇通往动荡年代中国的日常生活的窗口。而笔者的兴趣不仅只在于这些图像本身,还在于我们作为观看者观赏它们的目光。这些照片中内含着两种叙事干预。第一种是西德尼·甘博在二十世纪中国的游访和拍摄。第二种是我们作为二十一世纪的观众的干预。甘博在他对中国的多次访问中以各种不同身份参与到社会中。游客、旅行者、调查者或是基督教青年会(YMCA)成员,他在某些时刻同时身兼多重角色。在甘博的各种视角中,有三个将在此处做探讨:甘博在中国平民教育运动中的角色,他作为调查者的工作,以及他在摄影过程中的美学干预。另外,甘博也经历了一些中国迈向现代性的关键时刻。他和他的镜头因此也成为了这一转变的重要见证。

当时的中国以飞速的变化进入了一个崭新时代。清帝国已让位于共和政体,广受欢迎的领袖孙中山已经出现,对人民创建新政权的动员也已全面发起。我们可以在社会-政治变迁的运动中看到历史时间的行进:比如,黄包车夫罢工推动了五四运动。从君主制向共和主义的转变由此被人民的社会动员与运动所激发(2和图4)。伴随政权的变更,我们也能看到各类体系的变化,例如平民教育运动(图5)或监狱系统(图8)。在个体层面,被静物摄影所捕捉到并冻结在时间里的相貌神情也不断发生着改变。那些甘博出于对记录街头生活的痴迷而捕捉在赛璐璐胶片上的黄包车夫与农场工人,就是这样的例子,他们挑战着有关“城市生活”的刻板印象。因此,是运动定义了这一时期,无论是大规模的、横扫整个国家的制度与结构变化,还是这些改变对个体产生的影响。然而,这种变化是如何从环境中产生的呢?

例如,甘博在北京完成的人口普查,就是“个体”或人趋于消失的现代趋势的开端。人开始被替换为纸上的统计数据,而在实际生活中,机器的来临也威胁要把人的形体从城市街道上驱除。现代化真的意味着不再有人的工业化吗?比如在二十世纪的北京,有轨电车是否真的已经取代了人力黄包车?本文主要讨论的主题即是,人与其环境是如何随着其间的动态关系变化而发生互动的。这立即就让人想到了两个概念,它们是有关现代中国的讨论中特有的重要主题元素:一是运动,二是环境。运动通过前述两种干预手段有机地缠绕在现代化方案中;而更重要的是,运动孕育着变化。这些体制与个人的变化,正体现在人与其环境的关系中,因此这一关系对于本文的探究来说至关重要。因此,这两个概念将成为本文的先导。

然而,这里所说的运动究竟是指什么呢?甘博的作品处在对运动的历史学与美学阐释的交叉点上,其作品中的运动也有着双重作用,它既是一种现代性的历史决定因素,又是一种现代生活的美学条件。胶卷上捕捉到的物质身体,与变动着被缓慢推向“现代”的中国——这两种都是运动。对于中国来说,现代性就是明确脱离孔儒之道与君主制、转而借用“科学思维”亦即理性。二十年代的中国正是许多运动风起云涌、社会发生转变的时候,由劳动阶级超越于地方主义或本地狭隘主义之上的阶级意识建立所决定。其结果就是,黄包车夫、榨油工、机器厂工人以及铁路工人的工会运动被与中国社会变化的面孔联系起来。发动群众成为了当权者的首要任务。工人阶级的优先地位被历史地决定,而它也将通过劳动结构的重组以及对“身体”的动员来实现。“改变”是当时的颂词,而改变的载体则是动员与工人运动。这一时期也是公共福利体系发生转变的时候。医疗、教育与监狱系统都被改建并“现代化”了。交通被有轨电车与火车的到来所革新,而所有这些都迫使中国历史向一个全新的纪元行进。换言之,变化显著地重新定义着中国,而个人与体制层面的运动则是这一变化最好的体现。然而,我们又该怎样对运动进行美学的阐释呢?

在二十世纪欧洲众多使用运动、时间与人体概念进行实验的艺术家与理论家中,有一位是捷克斯洛伐克的舞蹈编导与理论家鲁道夫·拉班(Rudolf Laban),他把这些概念运用于他的艺术创作中。 拉班认为,“人为满足一种需求而运动。他运动的目的是某样对他来说有价值的东西。” 这种价值既可以是精神与思想的,也可以是一件物体的。他继续写道:“所以运动显著地揭示出许多不同的东西……运动可能被发出动作者的环境所影响。所以,譬如,行为所发生的社会语境会给行为者的动作染上颜色。” 亦即,环境塑造了运动。

这张照片以一位正在扬谷的男子为前景。这一运动被捕捉下来的不仅有男子的神态与他影子的位置,同时还有被反重力地定格在空中的叶子。我们看到,这幅被机械化地捕捉到的画面中,每个角落都显露出力效(effort)的痕迹。背景聚焦在另一个劳动着的人物身上,这里运动与力效显得更加明显清晰。在他的运动背后的力效是以保护一件“有价值的物体”为目的的,在这个例子中就是生存的开销。我们可以观察到环境如何影响了他的运动。他的运动被他的经济环境所决定;他也许是一位农场工人,而正是这一环境塑造了他身体运动的方式。从照片中可以看到,他的职业毫不含糊地从他衣服的折痕与褶皱中显露出来。就像这个动作一样,这些褶皱也是一瞬之间的,它们唤起了这一运动的短暂流逝性。正是这深埋其中的动态感让我们看到画面中心人物的流动性,而这一属性在下一张照片中更为强烈。

图2是有关北京黄包车夫的照片。他们的工作就是运动。他们的身影表现出运动的态势,而他们的劳动也被运动所定义——车上人与货物的运动,车夫自己身体的运动,以及时间的行进,而且黄包车夫也是为改变社会而被动员起来的劳动阶级之一。他们被他们的环境所影响,因为他们的劳动与力效是被经济环境的需求所塑造的。但同时,他们也通过参与工人运动而改变着环境。在图1与图2中,可以明显看到环境塑造着人的力效,但一如前文所述,中国当时正处于一个变化中的状态。那么环境是如何改变的呢?它又怎样对根植于其中的人产生影响?

Figure 4: Sprinkler wagon

泼水养路

562-3259

图3与图4捕捉的是动态的人物:在黄包车里坐着的,或是拉着黄包车的。但最重要的是,两张照片前景中的两个人物都在往路上洒水,以平息把整个城市搅得尘土满天的夏季沙尘暴。这两人是清洁卫生倡议行动的一部分,而这一行动本身则隶属于各体系更大规模的结构变动。然而,我们作为观众会怎样解读这两幅图像呢?拉班提到,运动是被力效所驱动的,而休息只是生命中仅有的过渡状态,因为力效与运动是人所特有的。 拉班认为,力效会被旁观者体验为节律。我们的目光并没有被训练得足以洞察运动背后的力效,而仅能将运动本身视作一种节律。因此,这种经验不仅属于运动所涉及的人,也属于那追随着运动中人物的力效与努力的另一人的目光。在两幅图像中,我们都能在中心人物的每一种运动中观察到内在的力效。运动的节律不仅通过他们的面部神态、也通过水的泼洒与舞动表达出来。水被反重力地移动并同时被固定在半空中,这一运动是反映性也是象征性的;事实上,它是人的运动与力效的延伸。更重要的是,之前的照片明确地展示了环境影响人的方式,但图3与图4则例证了一个与此反向的过程。人对水的随机应变突显出人驯服和改变其所处环境的方式。

另外,这两幅图像也强调了人与体系变化之间的关系,尤其与图?形成对比。在两组照片中,我们看到了同样形式的人的力效。人的经济与这一为了重组改建而进行的力效衔接了起来。虽然图1中的人物通过扬谷的行为贡献了他的劳动力,但他并未直接被纳入到变化系统中。而卫生倡议行动中的这两个人物却直接地与社会的结构性改变产生联系。而下面的照片甚至将更加明确地展现出,甘博的作品如何捕捉到人在现代化运动中被动员起来的方式。

图5至图6捕捉到了二十年代平民教育运动中的各种瞬间。图5描绘了参与平教游行的学生,而图6则涉及到了本文所思考的问题,即二十世纪中国的改变社会运动中特有的对群众的动员。甘博参与了晏阳初的平民教育运动,并积极记录下了其意识建设与社会动员的努力。他那些有关学校与YMCA动员倡议的照片充分证明了他对这些结构变化的兴趣。这些照片不仅让我们了解到当时教育系统中正发生着的结构变动,也改变了我们对于二十世纪社会运动与动员的解读,尤其是我们关于其对身体、亦即对人的组织与构建的思考。在有关监狱、学校和医院的照片中,我们能看到身体是如何被规训、被治理、或是被它们身处的体系所操纵的。身体被变得整齐划一,并能被轻而易举地归类,就像统计表上干净整齐的一列。当我们分析下面这张照片时,这一事实在视觉上变得更为明显。

在图7中,我们看到儿童被组织、排列成整齐的行列。照片中所捕捉到的个体性的表达被校服与制度化行为强加其上的同质性所破坏。甘博不仅捕捉下了这一瞬间,而且也通过他的调查活动参与实现了这一场景。因为,迈向“现代性”最初的步伐之一就是,用数字和统计数据来代替人。 一旦人被装进整洁的列表中,控制与规训就能开始了。这一论述在有关监狱的照片中将体现得更为充分,比如图8。

人也可以是工厂里的工人。然而,这是一所监狱,这个事实瞬间就把这一空间转化成了一个令人联想到学校的场所。可以看到,这里的囚犯在织布:这是一个重新进入社会的场所。这里的情况不应被误解为监狱系统中的主流。因为照片中的这个监狱是一个进行训练与获得技能的场所,与中小学或大学相似。然而,它与教育系统关键的不同在于规训被实行的过程。但重要的是,身体都被改变了,或是被体制结构变化所影响了。当然,学校和监狱是在非常不同的社会文化语境中运行的,但无论如何,它们在照片中的这一时刻还是被撼动它们的社会变化捆绑在一起。而比人与不断变化的结构更为显著地改变了环境的,则是大规模机械化的开始。

这是一幅来自新中国的照片,一个机械化的、“现代”的社会。黄包车夫要被机器所取代了吗?城市的空间能完全转型以容纳这个现代野兽的居住吗?这样一种转型又将对人产生怎样的影响?在图9中,有轨电车成了中心角色。人被边缘化,甚至被变得没有人性了。与前述照片不同,我们的注意力并没有被引到人物上,而是被引到机械的象征物上。对于拉班来说,运动可以是自愿的,也可以是非自愿的——亦即不涉及一个有意识的决定。他认为,非自愿的运动尤其根植于现代社会,人类被纳入工业之中。人变成了机械工业的一部分,而他们的运动也因此变成自动化的——作为系统一部分的个体在进行运动时没有任何有意识的思想或意图。 对于拉班来说,运动或力效被榨干了生命力,而这生命力正是作为行为者的人。在参与重复性动作时,人发现自己变得仅仅是机器的一部分,被剥离了他们自己的生命能量。机械化把人从整个图景中赶出。我们真的会在中国看到这个过程逐渐展开吗?

此外,拉班认为,在古代世界,运动是建筑、绘画和雕塑等各种艺术形式背后的粘合力。运动是我们日常生活与创造过程的核心。而现代社会的条件对于他来说是背离这一观点的,因为人的生命能量被机器榨干了。节律和运动本应是我们生命中不可分离的部分,现在却远离了我们的日常机械生活。这些照片中的人真的是冷漠的吗?机器真的已经占领了整个社会吗?在中国的社会语境下,城市中人的建筑已被工业的、机械化的建筑所取代了吗?现实是,中国在创造着它自己的现代性。至少在拉班的欧洲语境下,现代性就是用机械运动取代人的运动。机器频繁地被用作现代性来临的信号,而总是以人的缺失为代价。然而,中国的情况却很独特,因为是人塑造了它的现代性;机械从来都没能成为人的替代品,这在甘博的作品中就有例证。有轨电车确实是置换了人力,但人仍然填满了、甚至冲破了它的边界。黄包车夫是整个社会中的关键环节,他们和汽车、或是和平教运动的学生并行在同一个舞台上。在照片中我们可以看到一个工具,即那个干草叉,但能有效使用它的依旧是人。黄包车夫是变动的环境中充满活力的一部分。体系是被人手所改变、重建。归根结底,是人在推动着一个新的中国!

人从来没有被完完全全地从整个图景中分离出去;他总是找到新的途径把自己插入到“现代”这个概念中。冒昧地进一步说,甘博的作品也是一种机械化的行为——用相机捕捉人。但是它的角度,或说视野本质上仍是属于人的。这个视角是属于甘博的,他是又一个影响了人们如何记忆现代中国图景的人。因此,人不仅是照片的社会语境与内容里不可或缺的一部分,而且也是照片的创作中不可或缺的一部分。所以在此用一幅人手所创造、但最终还是一种机械再现的图像来作为结尾是十分合适的。在这张甘博所拍摄的照片中,同一个画面就整合了与相机捕捉人的运动和流动性有关的若干关键概念。看起来这是在火车上拍摄的照片,但它却呈现了另一种交通方式:船。它完美体现了独特的中国现代性的双重条件:人和机械化。火车让我们联想到撕裂自然风光的机器,然而船上用其自身力效驱使船运动的人却又让自己成为了谱表的另一头。两者同时形成对比,但又泾渭分明地结合在一起,创造出本文所定义的中国现代性。

[i] For more read: Tsin, Michael Tsang-Woon. Nation, Governance, and Modernity in China : Canton, 1900-1927. Studies of the East Asian Institute, Columbia University. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1999. And, Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China. 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999.

[ii] For more read: Laban, Rudolf von, and F. C. Lawrence. Effort. London,: Macdonald & Evans, 1947. And, Laban, Rudolf von, and Lisa Ullmann. The Mastery of Movement. 3rd ed. Boston,: Plays, 1971.

[iii] Laban, Rudolf von, and F. C. Lawrence. Effort. London,: Macdonald & Evans, 1947.p.5.

[iv] Ibid, p.8.

[v] Ibid, p.12.

[vi], Laban, Rudolf von, and Lisa Ullmann. The Mastery of Movement. 3rd ed. Boston,: Plays, 1971.p. 2

[vii] Ibid, p. 5.