Biological Art: The Next Frontier in Art or an Ethical Disaster?

Author: Sheel Patel

Contemporary biological art, defined as the usage of live tissues, organisms, and life processes to produce artistic pieces is creating things like living literary organisms and glowing rabbits. This could not have taken place without the surge of biotechnology and genetic manipulation that has become common in today’s scientific world. The implications that surround this technology are vast and truly show why Bioart is such a powerful, yet controversial topic today. We have now entered a time in society when artificial genes can be inserted into progeny in order to display certain characteristics. Where frozen sperm cells of a diseased father can be used to fertilize an egg and produce offspring, years after the death of the donor. What happens if someone learns and decides to control genetic manipulation and begins to hold physical and political power? Ideas and innovations like these are currently at our fingertips and the ethical issues stemming from them are equally important to talk about. Surrounding bioart is a sea of controversy and drama. Without a pure definition of what the art entails, the room for public outrage and controversy is high. Through good implementations of bioart one can see the vast benefits a living medium has in art, but through highly controversial implementations one can see the possibly detrimental side. Society must decided where to draw the line. This essay will examine the benefits bioart brings in projecting messages to its viewers along with the detriments and ethical dilemmas it raises, in order to interrogate the use of biotechnology outside of the scientific community. It will delve into this interrogation by considering many different forms of bioart including DNA bioart, body augmentation bioart, and biometric art visualization and their effects, positive and negative, on the viewers and the ethical issues they bring up.

BioArt: A loose definition

Before delving into the ethical quandaries and artistic innovations that Biological Art entails, we must view the evolution of this art form and its definition and boundaries. General art must be defined in order to see the characteristics bioart shares with the broad field and where it may differ. Webster’s Dictionary defines “Art” as “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.” From this definition it can be inferred that art is generally not seen to serve a functional purpose, like many scientific discoveries, rather it is to serve an aesthetic purpose and relay emotional messages to the viewer. Bioart seems to be breaking down this static definition of art with some of its implementations. According to Eduardo Kac, a contemporary artist and BioArtist, bio art employs one or more of the following approaches: “(1) the coaching of bio-materials into specific inert shapes or behaviors; (2) the unusual or subversive use of biotech tools and processes; and (3) the invention or transformation of living organisms with or without social or environmental integration”.1 This third characteristic is the most interesting as we delve deeper into using biotechnology and it is easy to see the ethical dilemmas that Bioart faces. Why is bioart such a growing sector of art and why is it so powerful? It’s power inherently lies from the versatility of the media bioart uses and the affordances that come with these different media.

Revolutionary transitions in media and technology have always brought about new ways for artists to express themselves, the most evident being the transition from radio (audio) to television and video. The same can be said with the immense surge in Biotechnology in the past few decades. Techniques like genetic cloning, efficient genome mapping, and advanced knowledge of protein synthesis are just some of the major advances science has made in recent years. These advancements in Biotechnology have opened up a plethora of opportunities for artists to exploit, using their full creative potentials. The options are limitless and many scientific boundaries that were thought to be static have already been broken. For example, it was well documented that Human DNA is comprised of 4 distinct nitrogenous bases that encoded genes, and life. Scientists have already produced unnatural forms of DNA, effectively expanding the number of bases from the well-known four to six. Other examples are the creation of novel amino acids leading to the creation of unnatural proteins.2 Examples such as these are just a few of the vast number of innovations science has opened up to biological artists.

Historical Trajectories

Bioartists literally work with living media, dubbed Biomedia, and produce living creations and forms of art that were previously impossible to do. Although it may seem very recent, Bioart and its biotechnological foundation has stemmed from centuries of experimentation. Bioart has morphed completely throughout history as our understanding of biology has increased. This metamorphosis has led this art form into facing larger ethical issues than those early bioartists faced. Today it is very well believed that life is ‘plastic’ and that it can be manipulated in many ways through the usage of biological science techniques.7 But this idea was slowly uncovered, dating back thousands of years BCE in Ancient China, where grafting was used as an agricultural technique. Grafting, or the idea of taking a part of one plant species and homogenizing it to grow with another, was used by the Botanist Theophrastos in 325 BCE to grow ‘hybrid’ plants.2 This can be seen as one of the first usages of genetic modifications, which today have evolved to genetically modifying humans themselves. The foundations of bioart itself began to make its way onto artists pallets in the 16th century with artists around the world painting portraits and paintings of people and figures that intersected the boundaries between ‘traditional beauty’ and the ‘true human form.’ Examples of this could be seen in the piece titled Portrait of a Girl Covered in Hair (1594) by artist Lavinia Fontana and The Bearded Woman Breastfeeding (1631) by Jusepe de Ribera.

Both of these pieces showcased models with hormonal syndromes and their effects on the body, but were revered in the art community.14 Although they do not seem to fit with the contemporary definition of bioart, a definition consisting of physical biological manipulations and modifications, these pieces served as stepping stones to what could be done with biology with the proper knowledge and technology. A larger jump to actually modifying living materials for artistic purposes was taken by Edward Steichen in 1936, during his groundbreaking exhibition of flowers that he had created at the Museum of Modern Art. With this exhibit, Steichen was the first modern artist to create a new living organism by using both traditional botanical methods and artificial methods. He created new flowers by hybridizing them by hand and using specific chemicals to cause mutations to their genes and thus invoke specific alterations to their appearances.14 This was a large step in stating that genetics and gene/biological manipulation could be used as a viable art medium. The next step in Biological art could be seen in the use of live animals to actually be part of the art itself or in the first case, create the art. In 1910, the journalist Roland Dorgeles successfully created three oil paintings that were created by a donkey who had a paint brush attached to its tail.4 Other examples of animals in art were seen in some Salvador Dali exhibits that used shark and other animal heads, superimposed on a mannequins body.14 Again like the hormonal syndrome oil paintings, these pieces do not necessarily fit the contemporary definition of bioart, rather they serve as precursors to bioart by integrating animals into the art-making processes.

The use of bodily fluids also dates back to the 19th century. In the 1960’s, blood and urine were used as a main component in paintings describing Vienna Actionism. The most famous example could be seen with Andy Warhol who created a series of “Oxidation Paintings,” in which he utilized a reaction between a copper based paint and his own urine.14

Examples in Contemporary Literature and Society

DNA BioArt

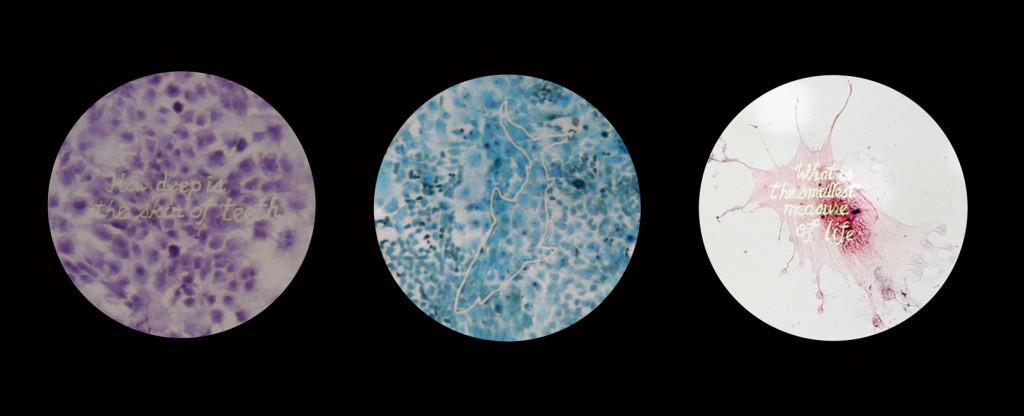

The beauty and effectiveness of contemporary biological art lies in its versatility. Its ability to use and manipulate a wide range media, allows bioart to extend various messages to its viewers. But this versatility and manipulation also lends itself to the ethical controversies that bioart faces in today’s society. Some of the most interesting contemporary examples of BioArt can be seen through the manipulation of the human body and genome. In one of his most famous experiments entitled ‘Genesis’, Eduardo Kac explores the relationship between biology, religion, information technology, and ethics. The methods of the experiment consisted of Kac synthesizing his own gene by translating a verse from the biblical book of Genesis. This gene was then translated into Morse Code and the code was converted into the a sequence of the four canonical base pairs: ‘A’,’T’,’C’, and ‘G.’ The translated sentence taken from Genesis read, “Let man have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.”15 This was chosen due to its message regarding man’s inherent control over nature and the sentence is very fitting with the overall objective of Kac’s experiment.

The gene was then transformed or transferred into a bacteria cell line, and the cell line was allowed to proliferate, and thus mutate, before the gene was extracted back and resequenced to view the changes. The ‘mutated sentence’ read “Let aan have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the fowl of the are and over every living this that ioves ua eonn the earth.” 15 The purpose of this piece is much more symbolic than it is aesthetically pleasing. With the mutation of this sentence, Kac showcases the idea that the inherent meanings of things that we experience and read are often plastic, they often change and mold over time just as nature does. Another equally interesting genomic BioArt piece can be seen through the piece titled ‘Xenotext’ by Christian Bök. In the nine year long experiment, Bök has been attempting to write a short verse of poetry and translate it into a gene, a very similar process to what Kac did in his piece. The difference with this piece is that when the gene is integrated into a living cell, the cells will inherently produce a novel protein that can be further transformed from progeny to progeny and continue to change and mutate as the generations grow. Thus, Bök will not only have created a medium in which to store his original poem, but also have created a mechanism or ‘biological’ machine that can write new poetry by itself.9 This piece has very interesting implications in the realm of poetry and literature, which is why it has had such a large impact in BioArt. If a living cell can be cultured to spit out and produce novel poetry, could we eventually live in a society where humans are no longer needed to produce new thoughts, and works of literature?

As Bök says, ‘a poet might become a breed of technician working in a linguistic laboratory.’9 The other interesting idea stemming from this piece is the storage of ideas. Has Bök come across an eternal medium? Using living cells, bacteria, or parasites to ‘hold’ messages in its genetic code could be a way to make sure that a message lives forever, even after civilization has crumbled.

Body Augmentation BioArt

The idea of BioArt has been talked about in literature since the dawn of the science fiction genre. The idea of using or modifying one’s body to express oneself has been a fascination for science fiction writers. This can explicitly be seen in the novel Neuromancer by William Gibson. Neuromancer details a society where biological art and bodily modifications have taken over, and have augmented the line between reality and cyberspace.16 With humans being modified with both biological and mechanical enhancements, the society transforms into a population that feeds off of jacking into cyberspace or altering their minds in reality.15 Bioart can be seen everywhere in the novel, where people have modified and altered their bodies to an almost unrecognizable form. An example can be seen with the character Molly Millions, who through extensive surgeries has acquired prosthetics, fingernail implants, and mental switches that render her a ‘super-ninja’ assassin. This can be seen when the main character Case, a computer hacker/cowboy, meets Molly for the first time. He notes, “She held out her hands, palms up, the white fingers slightly spread, and with a barely audible click, ten double-edged, four-centimeter scalpel blades slid from their housings beneath the burgundy nails (Gibson Chapt 1).” Her biological modifications serve specific purposes, ones that make her efficient in the realms of stealth and combat but many of them are also cosmetic. The idea of biological alterations can also be seen through another character, Julius, who has extensive surgeries done to him, which switch out his DNA and allow him to continue living way past the age of 150. “Julius Deane was one hundred and thirty-five years old, his metabolism assiduously warped by a weekly fortune in serums and hormones. His primary hedge against aging was a yearly pilgrimage to Tokyo, where genetic surgeons re-set the code of his DNA, a procedure unavailable in Chiba (Gibson Chapter 1).”

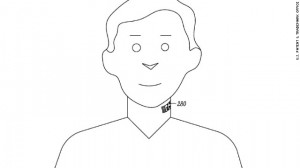

These examples shown in the novel again detail the convoluted line between bioart and the actual changing of the human form to something that may not be human anymore. To an extent, the bodily modifications on Molly can be considered ‘art,’ in the classical sense that her prosthetics and elongated fingernails serve aesthetic purposes. But these modifications also serve significant functional purposes that allow her to be an assassin, therefore if Molly is an example of bioart, one can see how bioart continues to break the boundaries and redefine the definition of ‘art.’ Other sci-fi examples of this hazy division between bioart and actually changing the human can be seen in the novel Ebocloud by Rick Moss. Ebocloud details a society in which people have become members of a ‘cloud’ society and the idea of loneliness is completely abandoned.17 This works through the setup of ebocloud.com, which when used, allows people to be assigned to ‘ebos’ or groups that serve as pseudo-families and strive for humanitarian gains. The purpose of establishing these close-knit networks is to work with other people to build a better planet (Moss 57). Unlike Facebook, “ebocloud pulls you out of yourself rather than competing for who has the most friends” (Moss 203). Slowly, the cloud continues to expand to a point where people begin adopting “dtoos,” digital tattoos that can map the human brain and send signals to and from the cloud. This is where Bioart can be seen as a feasible extension of the human body that could become a reality in the near future for the majority of people. The digital tattoo not only marks the person’s body for recognition by other people in the same ebo, but it literally can control their brain functioning and alter behavior. This is an example of where biological art can overextend its boundaries and cause some ethical dilemmas. In the novel, many examples of good can be seen extending from ebocloud and the dToos. Examples like the ‘kar-merit’ system, a system that rewards those members who make humanitarian gains and strive to help others. But as the novel progresses, the feasible downfalls of the system are elucidated when the few people controlling the cloud fall into corruption, and begin to control the population through the “dToos.” When biological art extends further from just simply modifying or augmenting the human body’s appearance to actually controlling the way we function and think, it’s easy to see the quandaries that can be caused. Essentially with dToos, all of human knowledge and experience can be pooled into the cloud and projected back, sharing the knowledge with everyone. This leads to an extremely efficient, intelligent, and compassionate human race where everyone is skilled and animosity is essentially eliminated between people. This however, is if the ebocloud was to work perfectly. The ethical issues that are raised generally have to do with the downfalls of a system like ebocloud. What if someone cloud controls the minds of everyone connected to the cloud, and fosters artificial relationships between people, groups, ebos, and nations for ulterior motives? This example from the sci-fi novel Ebocloud by Rick Moss delves into one of the various ethical issues brought up by bioart, caused by the loose definition and undefined boundaries that biological art entails. Both of these sci-fi examples of bioart do serve a significant purpose, that I believe mirrors the general purpose of actual bioart. By showcasing futuristic examples of biological modifications in humans and their possible ramifications, bioart and fictional representations of bioart, draw attention to the way that the human race is moving. This idea that has been relayed in science fiction novels may become reality in the near future. According to CNN, scientists at Google have created digital tattoos of their own that, when implanted in the neck, could allow users to relay messages and signals to their smartphones without needing a headset.6

Ideas like ‘dToos’ from Ebocloud and actual prototypes of similar tattoos from Google show what society could be like if we continue to technologically evolve and modify the biological aspects that make us human. And they exhibit what humans and our society could transform into if the line, between bioart and significant human modification, is not drawn.

Biometric Art Visualization

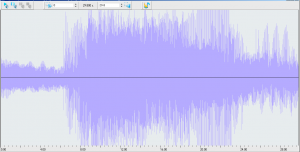

As shown, bioart spans a wide range of disciplines and can incorporate a wide variety of media in order to get specific messages across to the viewer. One of these messages could be to inform or detail a serious medical condition, unknown to most people. This was the goal in the seizure visualization piece I created. Seizures affect millions of people around the world and can be very harmful to normal bodily function and can in some cases even cause death. The aim of this project is to visualize the occurrence of seizures using Electroencephalograph (EEG) data. By visualizing this data through music, one can vividly hear the effect a seizure has on a patient’s brain and how large of an impact it has on normal brain function.

The piece consists of open source EEG data of a patient who underwent a seizure during a recording session. The EEG data was taken and read using EDFbrowser, and was converted into a “wav” file for further analysis. Of the 40 minute EEG clip, a 30 second clip of the seizure activity was taken and converted into the “wav” file. After conversion, the “wav” file was able to be read by a host of audio editing programs including Audacity, an open source editing platform. Using Audacity, the “wav” file EEG data was able to be visualized and converted into a sound wave which could then be translated into a MIDI file and thus be converted into audible music. In order to do this, the program WidiPro was used which is windows-based software that takes recorded music in an assortment of formats, and translates it into a MIDI file by recognizing individual notes through the audio’s waveform and pitch spectrum. As shown in the audio file of the clip, during the seizure activity there is a drastic change in the pitches, volume, and frequencies of the notes.

The notes seem to become more sporadic and disorganized which signifies the severity and overall chaos that occurs in the brain during a seizure. This can further be visualized through the audio visualizer that was utilized to play the final translated audio file. However, there were many limitations to this bioart piece. Widipro software was designed to analyze and translate general music in the audible frequency spectrum, therefore when analyzing a “wav” file converted from EEG data, the program had difficulty picking up on and recognizing majority do the file.

In future pieces, it would be beneficial to create and write a tailor-made program specific to analyzing EEG data. Nevertheless, this piece aims to do what most bioart pieces set to do in taking an unusual biological medium, in this case EEG data, and re-mediate and re-visualize it to show the reader a pattern that may not have been seen before. Through the sheer sporadic changes in pitch, volume, and the ominous thrashing of keyboard keys the viewer can distinctly see the dangers people who suffer from seizures face and the internal neurological mechanisms that go awry. This biometric visualization serves as a different representation of bioart, a representation that is not as invasive in the sense of altering DNA or the physical body. It takes biometric signals radiated from the human body and exhibits a pattern for the untrained person, in order to show the destructive power of a traumatic neural event. Again, this serves the major goal of bioart in uncovering unseen patterns from biological data, modifications, etc. and using these patterns to portray a message to the viewer.

Darker side of BioArt

With an understanding of what bioart entails and the multitude of characteristics and mediums that it can use, one can see the power it holds. With its often grotesque and novel nature, the messages biological art can portray are often shocking and eye opening and it is a very efficient and creative form of art. But with these positives comes the darker side of biological art and the ethical dilemmas biological artists must face. Manipulating living organisms of any kind, as with the pieces by artists like Kac and Bök, inherently dives into the ethical issues of life, death, and the motives of doing such experiments. Often people become nervous when hearing about bioart or biotechnology, as Terminator-esque visions of the future fill their minds. French philosopher Michel Foucault was one of the first to address the issue of bioethics and what experiments in the bioart field along with biotechnology in general may entail. Foucault argues, ‘‘the emergence of the health and physical well-being of the population in general’’ becomes ‘‘one of the essential objectives of political power.’’11 He believes that with the continued manipulation of biology and biotechnology, something many biological artists are doing, we may develop into a world where political power stems from being able to control or manipulate the physical and mental health of a population. This is an issue that could be seen in the novel Ebocloud by Rick Moss, that was discussed previously. With the power to control virtually anybody with the ‘dToo’ or biological tattoo, political power could be seen in the hands of those who controlled the biological power. In that case, biological power directly correlated to political power and power over a large population of people. Along with the ethical issue of directing power through biological technology, one of the largest issues with bioart is the idea that living organisms are being manipulated for the sake of art and aesthetics. Many people view bioart as an unnecessary use of living organisms compared to scientific research, which has the goal of improving the quality of peoples’ lives. Bioart is often considered unethical by scholars because of the purely aesthetic nature behind it. Professor Frances Stracey of University College London believes this and states, “Bio-art is least successful, and most contentious, when the science is reduced to mere aesthetic spectacle, and no account is taken of the specific or paradigmatic differences that affect how one discipline is mediated through another.” 8 He details this aesthetically driven problem of bioart and expresses his concern on the matter.

Examples of Ethical Controversy

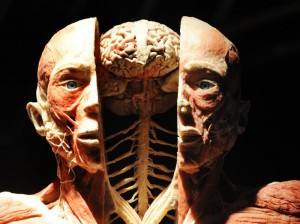

So where can we draw the line? Where does biological art over-extend its boundaries and become a public indecency and cause detriment to its viewers rather than conveying a significant point? Questions like these are at the front lines of the bioart field and they can only be answered by looking at the past and reflecting on previous art pieces or by speculating the future in the way novels like Neuromancer and Ebocloud have. The two sides of this debate can be seen through the art exhibitions of Gunther von Hagens, a physician and anatomy lecturer at the University of Heidelberg in 1998 and Rick Gibson in 1984. In 1998, the State Museum of Technology and Labor in Mannheim, Germany displayed Von Hagens exhibit titled, Koperwelten or “The Human Body World.”

The exhibit consisted of over two hundred preserved human cadavers along with their body parts that were prepared through a special embalming process called plastination. This allowed the bodies and organs to appear as if they were in-vivo. Many of the corpses were displayed to be doing activities such as fencing or jumping and Von Hagens even displayed a 5-month pregnant woman with a fetus in the womb.10 This exhibit sparked a large amount of controversy from both the public and the German Association of Anatomists, who described the show as “perverse and voyeuristic.” In order to deflect controversy away from this, the Mannheim Museum employed medical students to be tour guides of the exhibit and give explanations of the physiology and anatomy behind the exhibit.10 Even with the large amount of community pressure to take down the exhibit, the city of Mannheim refused and stated that “the scientific value” of the exhibit made it worthwhile. This example shows how the boundaries between biological art and science can be convoluted. In this case Von Hagens sought to display the human corpses as art pieces, shown by his use of putting them into different poses. But with the significant controversy stirred up by both academics and the community, the museum had to shift the exhibits image towards the scientific side in order to ease the public. With this example it appears that the public is more likely to accept something that is gruesome, raw, or shocking in nature if it is considered science opposed to it being considered as an art form. This brings up very interesting points in terms of how art should be judged. To what ethical and moral standards should art be judged versus science? This question can be better seen through the 1984 piece by British artist Rick Gibson titled Human Earrings.

Gibson decided to create a sculpture “to show the place of humans in society and how we treat human beings,” by obtaining and hanging two, rehydrated 10-week old fetuses off of a female mannequin head as earrings.12 Following this exhibit, both Gibson and the owner of the British gallery were prosecuted for ‘outraging public decency.’ Gibson tried to plead that the art was in the public good and should not be prosecuted but this plea was denied and eventually he was fined $875.13 The judge stated that “in a civil society there has to be a restraint on the freedom to act in a way that has an adverse effect on other members of society.” 12 The trial of Rick Gibson provides a very interesting look on biological art and the law along with the divide between bioart and science. Unlike Von Hagens, Gibson did not change the image of his exhibit to appear as it was scientific in nature. Gibson retained the idea that the Human Earrings served an aesthetic purpose in showcasing, in a raw and shocking way, how society treats other human beings. But the ethical issue lies in the way that art should be judged by the law and whether science should be judged in the same manner as well, if there is a distinction. If the piece had been ‘classified’ as scientific in nature, then it is safe to assume that the controversy would not have taken Gibson to court. But due to its artistic nature, and the view of many that Gibson was exploiting and disturbing biological constructs lead to an outrage and prosecution.

The Debate Continues

As shown, the ethical issues surrounding biological art span all aspects of society affecting artists, policy makers, the judicial systems, and scientists alike. It is up for highly contestable debate whether art pieces like Christian Bok’s Xenotext or Eduardo Kac’s Genesis are exploitations of living organisms for the pure purpose of art or if they are valid manifestations of art, used to deliver messages to the public. Even using EEG data and converting it into an auditory listening experience could be debated as ‘exploiting’ scientific data in order to make an aesthetic art piece. One that serves no other purpose than to rehash biological data into ‘jarring sounds’ and ‘pleasing colors.’ Overall, biological art is a highly controversial field in contemporary art. With some usages of bioart, the line between ethical and unethical is often crossed or bent. Examples like Gibson’s Human Earrings demonstrate this redefinition of borders, and the controversy this art form can stir up between artists, scholars, and the general public. Through other implementations and usages of media, bioart can be a provocative reminder of how life is modeled and represented compared to how it is valued, used, and disposed of. From the examples of bioart shown above, the pieces display patterns and messages that would be hard to convey with other media. Would demonstrating the idea that everything in our world inherently changes over time be as impressive if it wasn’t for Kac’s Genesis showing that even the most basic aspects of life mutate? Doesn’t an auditory representation of electrical brain waves show the sheer power and wrath of the human brain and its appearance when things go wrong? It is understandable for certain biological art pieces to draw a lot of controversy and stir up ethical issues, but when implemented correctly and held within societal boundaries, bioart can be the most efficient and eye-opening way to get some very large messages across. It is safe to say that bioart is an extremely powerful media and implementation of art, that can get significant messages across to viewers in ways that were previously unused. Whether some of these messages are necessary or ethical will continually be under scrutiny. The debate will continue as long as new biotechnologies and new bioart pieces continue to emerge. It will be up to us as a society to decide and form a boundary between acceptable bioart and its detrimental and exploiting counterpart.

Citations1Kac, E. (2007). “Life Transformation” Art Mutation. Signs of life bio art and beyond (p. 163). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

2Kac, E. (2007). Blood and Bioethics in the Biotechnology Age. Signs of life bio art and beyond (p. 115). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

3Kac, E. (2007). Bioethics and the Posthumanist Imperative. Signs of life bio art and beyond (p. 95). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

4Kac, E. (2007). Open Source DNA and Bioinformatic Bodies. Signs of life bio art and beyond (p. 31). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

5Bioart, Ethics And Artworks. (n.d.). Masters of Media. Retrieved December 6, 2013, from http://mastersofmedia.hum.uva.nl/2012/04/18/bioart-ethics-and-artworks/

6Gross, D. (2013, November 13). Google patenting an electronic ‘throat tattoo’. CNN. RetrievedDecember4,2013,from http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/12/tech/innovation/google-throat-tattoo/index.html

7Kennedy, R. (2005, July 5). The Artists in the Hazmat Suits. NY times, p. 2.Site Search. (n.d.). The Xenotext Experiment. Retrieved December 6, 2013, from http://www2.law.ed.ac.uk/ahrc/script-ed/vol5-2/editorial.asp

8Stracey, F. (2009). Bio-art: The Ethics Behind The Aesthetics. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 10(7), 496-500.

9The Xenotext Works. (n.d.). Harriet The Blog RSS. Retrieved December 6, 2013, from http://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2011/04/the-xenotext-works/

10Korperwelten catalogue of the exhibit at the Mannheim Museum of Technology and Work, Oc- tober 30, 1997 to February 1, 1998.

11Michel Foucault, ‘‘The Politics of Health in the Eighteenth Century,’’ in The Foucault Reader, ed. Paul Rabinow (New York: Pantheon, 1984), 277.

12‘‘Two Face Charges in Britain for Showing Human Foetus Earrings,’’ The Reuter Library Report (January 31, 1989).

13John Weeks, ‘‘Art Pair Fined over Foetus Earrings,’’ The Daily Telegraph (London) (February 10, 1989): 3.

14Kac, E. (2007). Introduction Art that Looks You in the Eye: Hybrids, Clones, Mutants, Synthetics, and Transgenics. Signs of life: bio art and beyond (2. printing. ed., p. 14). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

15Kac, E. (n.d.). Genesis. Genesis. Retrieved December 6, 2013, from http://www.ekac.org/geninfo.html

16Gibson, William. Neuromancer. New York: Berkley Publishing Group, 1984. Print.

17Moss, R. (2010). Ebocloud: a novel. Upper Montclair, NJ: Aerodyne Press.

18 www.art-prints-on-demand.com

19 http://www.artexpertswebsite.com/pages/artists/fontana_la.php

20 http://www.dertimm.de/2009/06/01/zwischen-faszination-und-ekel/

21 http://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2011/04/the-xenotext-works/

22 http://www.rickgibson.net/freezedry.html

23 http://www.fondation-langlois.org/html/e/page.php?NumPage=278

24http://www.ecuad.ca/sites/www.ecuad.ca/files/users/350/work/88757/4Symbi%20WEBSITE.jpg

25 Zach Corse — “Fountain” Music Visualizer