About This Project

“By which spring has this meadow been nurtured?”

So asked Abu Talib Kalim, a brilliant poet in the court of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1627-58), in rhapsody over an object that was apparently placed in his hands. [1]

The object was a sumptuous imperial album, a muraqqa’, not unlike the one I host on this site, in which I track the itineraries of the terrestrial globe in Mughal India.

Described by Elaine Wright as “a fine art cousin of a modern scrapbook,” the imperial muraqqa’ (Persian for “album”) was a collection of paintings and drawings (tasvir) and calligraphic works (khatt) assembled by a patron, usually the emperor himself, from some of the finest paintings produced by his atelier as well as others that caught his attention. [2]

Literally meaning “patchwork” in Arabic, a muraqqa’ was typically assembled by affixing a miniature-format painting (or a group of works) onto a thin card created out of many layers of fine paper, whose borders were decorated with intricate designs and other marginalia, which were then either loosely placed or bound between luxurious and ornamented leather or lacquer covers.

The art historian Ebba Koch has noted that a muraqqa’ is a book in form and a picture gallery in function. In the age of virtual technologies, a muraqqa’, such as the digital object I have assembled and curated, also becomes a highly mobile, portable, if virtual, picture gallery. [3]

The making of such albums has been traced to fifteenth-century Herat whence this practice spread across the wider Persianate world, alongside other arts of the book. Shah Jahan’s grandfather, Jalal al-Din Muhammad Akbar (r. 1556–1605), is said to have commissioned the first Mughal muraqqa’ consisting of the portraits of the grandees of his court. It was, however, in the reign of Akbar’s son and successor, Nur al-Din Jahangir (r. 1605–27), and the latter’s son Shah Jahan, that album making matured in the first half of the seventeenth century. In a classic Mughal muraqqa’, pages with facing paintings framed by decorated borders typically alternated with facing pages of calligraphy by some of the most renowned scribes of the Persian world. [4]

A royal muraqqa’ was a site of imperial choice and desire. Appearances to the contrary, underlying each album was a set of deliberations about works to include, and the order in which to present them. A typical album was a highly orchestrated product of years, sometimes decades, of thought, imagination, labor, and investment of resources. Some were clearly commissioned by one patron, the padshah (emperor). Others were inherited, reassembled, and supplemented, as they passed on from one generation to the next. They are all works of collaboration, at the very least between emperor, master painter, apprentices in the imperial atelier, and calligrapher. All the same, they should be perceived as sumptuous repositories of imperial self-fashioning, albeit heavily mediated by collaborators who translated individual vision into painted works of art.

A muraqqa’ is undoubtedly a work of art in itself, although until recently it has been dismissed as a motley and disorderly collection of this and that. As such, an imperial muraqqa’ allows us to take stock of the mighty Mughal emperor as connoisseur, collector, and curator, but also, as co-crafter of his own pictorial self that he sought to put on display.

The royal album was not an object that circulated widely. On the contrary, it was an artifact that was most likely selectively shared with a private circle of intimates and friends, and also quite possibly shown to men whom the padshah sought to impress, not least with opulent displays of his material wealth and powers of accumulation. The very nature of the object with its collation of small-scale paintings filled with intricate detail and minute calligraphy suggests a form of embodied “intimate” viewing that required intense concentration, touching and turning the page, pausing and contemplating, and turning once more. [5]

With the likely exception of an album compiled by Shah Jahan’s eldest son Dara Shikoh in the 1640s (likely as a gift for his wife, Nadira Begum), no Mughal imperial album is known to have survived into our times intact, making our analyses of this lost tradition quite speculative. Today, the paintings and calligraphic folios that once were part of such opulent works have been separated and scattered across the world. [6]

My digital muraqqa’ pays homage to this important and intriguing art of the book by mimicking some aspects of its form, even while adapting and updating it for a scholarly project of the twenty-first century. Like Jahangir and Shah Jahan’s grand albums, which have inspired my own, I too have brought together in these pages an eclectic array of paintings, prints, and photographs of objects spanning genres and historical time periods. I have attempted as well to digitally conjure up the spirit of the Mughal album by assembling and curating an artifact in which images are in dialogue with other images in a manner that demands contemplation and immersion, but also discussion and debate.

I make one significant departure from the form of the classic Mughal album in that, in my digital curation, pages with facing paintings do not alternate with facing calligraphic pages. In this regard, my digital muraqqa’ is closer to the format followed in post–Mughal India where the paintings of a former age of imperial grandeur were actively sought out, collected, and displayed by a new generation of admirers (and not just from the subcontinent) in reconfigured albums, some of which have survived into our time in the great museums of Europe and the United States.

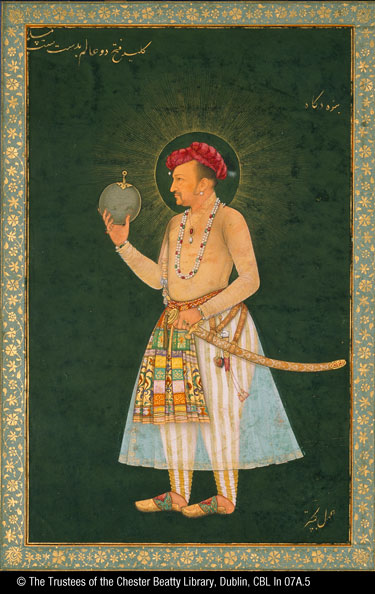

With the possible exception of one early seventeenth-century album (the so-called Shikarnama), dedicated to paintings depicting hunting scenes that were probably commissioned by Jahangir when he was still Prince Salim, Mughal albums were not generally thematic in nature. My digital muraqqa’, by contrast, focuses on the display of a single artifact as it appeared in paintings commissioned or collected by the emperor, or prints that came into his hands. This artifact has virtually left no verbal trace in the vast archives of the Mughal Empire, nor is there a material survivor. The only material evidence to the fact that it arrived and circulated in Mughal India is from the images that you see in this album.

That artifact is the terrestrial globe, a master object of modernity that since at least 1492 has served as the model of and for Earth, the planet whose surface we inhabit as sentient beings. The artifact first arrived in India at a time when the Mughal emperors were expanding their dominion across the subcontinent. It arrived both as representation and as object, carried over from a distant continent into India by Christian missionaries, traders, and royal emissaries. In this early period, the terrestrial globe appears to have been largely confined to the imperial court and its attached atelier. Hence my focus in this digital project on its fate there, despite the fact that I am not a specialist of this period on which there is extraordinary historical scholarship, from which I have benefited.

Supported by a grant from the Arts and Sciences Committee on Faculty Research and the Franklin Humanities Institute at Duke University, I have undertaken this project as a cultural historian interested in documenting cartographic practices in the Indian subcontinent. The paintings I have brought together in this album are complex entities and may be variously analyzed, but my primary concern is with “the calculated display” of the globe of the earth within the frame of each work. [7]

I have also undertaken this project as a work of public scholarship, with a keen interest in bringing these fine images and the superb interpretations on many of them to the attention of a wider audience outside academia. As such, I have cut back on some of the protocols of academic publishing, such as detailed footnotes, citations from existing scholarship, and exhaustive references. My project owes a good deal especially to scholars who work on Mughal art who have labored through the years on many of these fine paintings, only some of whose work I have been able to formally acknowledge in the pages of the album. Readers interested in exploring further can consult the list of references I provide on this website.

Not least, this is a project that uses the new tools of digital humanities to explore both the promise—and the limits—of online scholarship and curatorial work, which with pleasure I now share with you.

To view my album, please click here.

NOTES

[1] As quoted in Welch et al. 1987, 42.

[2] Wright 2008a, 80.

[3] Koch 2010, 279.

[4] The best scholarly analysis of the Persian album I have seen is Roxburgh 2005, which focuses on Safavid Iran. There is no comparable study of the Mughal imperial album, let alone of album making among high-ranking courtiers and other wealthy elites. For my work, I have especially benefitted from my reading of Losty 1982, 82–84; Welch et al. 1987; Bloom and Blair 2009, Vol. 1: 43–45; Losty and Roy 2012; and especially Wright 2008.

[5] Juneja 2001, 208, and Juneja 2009, 245-46. See also Moin 2012, 209-10.

[6] Losty and Roy 2012, 124-128.

[7] Brotton 1999, 82.