In a society where it seems like the power to create meaningful change on climate concerns is concentrated in the hands of few, witnessing the youth attempt to counter this dynamic is always inspiring.

Last week, members of Duke University’s Climate and Sustainability Office convened with students for a town hall meeting to discuss current progress, areas for improvement, and aspirations for the future. During this meeting, great emphasis was placed on the opinions and perspectives of students, as the leaders of the Duke climate commitment recognized the importance of their voices within this process.

The meeting began with two thought-provoking questions by Toddi Steelman, Vice President and Vice Provost for Climate and Sustainability, and Tavey Capps, Executive Director of Climate and Sustainability and Sustainable Duke: “What is one word to describe your feelings towards climate change, and what energizes you about climate change?”

These two questions immediately brought the room to life as students began to express their climate anxiety, fears, and frustrations, alongside the ways in which they hoped to one day see change. This passionate discussion set the stage for a deep dive into the objectives and goals of Duke’s Climate Commitment.

The Climate Commitment is a university-wide effort aimed at creating initiatives to correct our current climate crisis by creating a sustainable environment for all.

Within the commitment, there are five areas of focus: Research, Education, External Engagement, Operations, and Community Connections. The research sector is focused on connecting Duke’s schools across the board for interdisciplinary research. Education is geared towards ensuring learning occurs in and beyond the classroom. External Engagement focuses on informing policy and decision makers alongside engaging community members within this mission. Operations studies the food, water, waste, energy, and carbon supply chain on campus. Lastly, Community Connections asks: how do we authentically engage with the community and partners alike?

This commitment serves as a broad scale invitation for everyone to get involved, and Duke students did not hesitate to take advantage of this invitation. The town hall was organized through breakout rooms for the students to collectively share ideas.

The first breakout room was focused on the idea of communication. In this, students discussed the ways that they felt the commitment could best reach their peers on campus. Some proposed utilizing the popular social media platform, TikTok by creating short eye-catching videos. Others discussed using professors, posters, and BC Plaza to ensure engagement. Most agreed that email listservs and newsletters also held some merit in getting their classmate’s attention.

Above all, students came to the consensus that informing the student body would be one of the most important missions of the Climate Commitment.

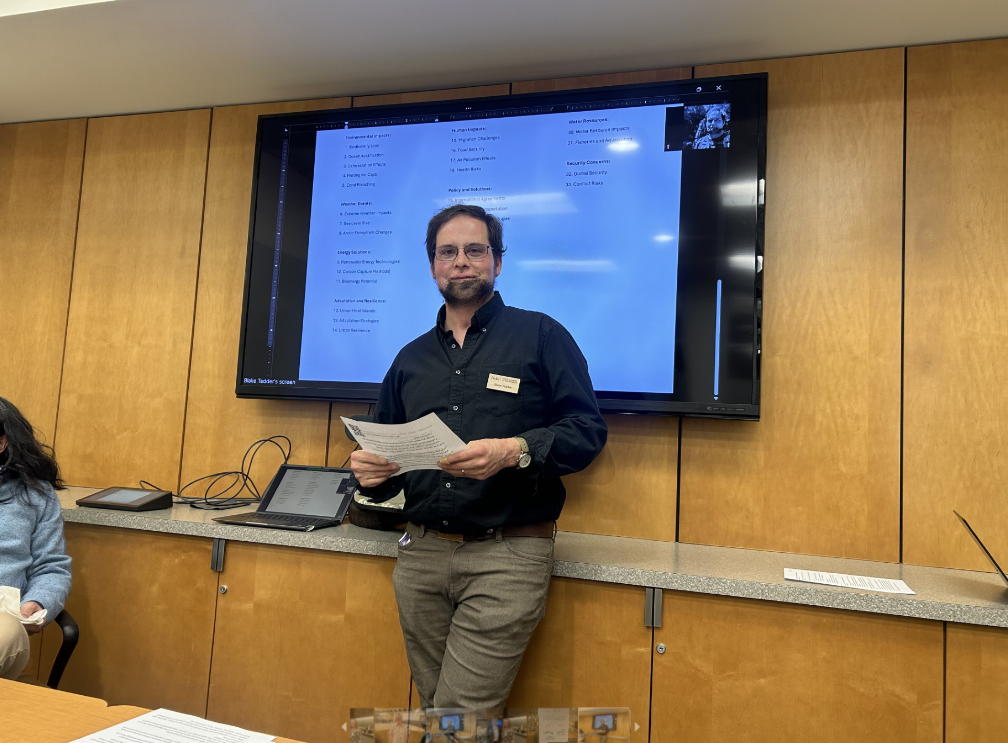

Following the communication session, I attended the research breakout room led by Blake Tedder from the Office of Sustainability and formerly the Director of Engagement at the Duke Forest. He asked again about the most pressing climate issue. From this, many students delved into issues surrounding biodiversity financing, carbon offsetting, access to clean water, and the ways climate change disproportionately affects marginalized communities.

Conversation about these concerns quickly bled into issues surrounding the larger prospect of interdisciplinary studies. Many students felt that this was best done through Duke’s RESILE initiative (Risk Science for Climate Resilience), Bass Connections, and even greater connection between Duke’s main campus and its Kunshan Campus.

The final room I attended was geared towards making the fight against climate change one that is inclusive and diverse. This talk was coordinated by Jason Elliot from Sustainable Duke.

The question that guided the discussion was: “How can we ensure our goals do not come at the expense of the community?” To this, students proposed a range of ideas. Chief among these were becoming more in tune with the needs of the community and finding ways to actively attend local farms, and other places in need.

In addition, many suggested diversifying speakers to ensure representation and voices from all parts of the community. Some students even narrowed in on engagement within our own campus, suggesting greater collaboration among groups such as the Climate Coalition, Keep Durham Beautiful, and Alpha Phi Omega to achieve these goals.

This town hall was simply one of many future engagements expected from Duke’s Climate Commitment in the coming years. While there is still much more work to be done, the diligent efforts of students and faculty alike make the future look promising in the fight against Climate Change.