Look at the nearest window. What did you see first—the glass itself or what was on the other side? For birds, that distinction is a matter of life and death.

Every year, up to one billion birds die from hitting windows. Windows kill more birds than almost any other cause of human-related bird mortality, second only to feral and domestic cats. Both the transparency and reflectiveness of glass can confuse flying birds. They either don’t see the glass at all and try to fly through it, or they’re fooled by reflections of safe habitat or open sky. And at night, birds may be disoriented by lit-up buildings and end up hitting windows by mistake. In all cases, the result is usually the same. The majority of window collision victims die on impact. Even the survivors may die soon after from internal bleeding, concussions, broken bones, or other injuries.

Madison Chudzik, a biology Ph.D. student in the Lipshutz Lab at Duke, studies bird-window collisions and migrating birds. “Purely the fact that we’ve built buildings is killing those birds,” she says.

Every spring and fall, billions of birds in the United States alone migrate to breeding and wintering grounds. Many travel hundreds or thousands of miles. During peak migration, tens of thousands of birds may fly across Durham County in a single night. Not all of them make it.

Chudzik’s research focuses on nocturnal flight calls, which migrating birds use to communicate while they fly. Many window collision victims are nocturnal migrants lured to their deaths by windows and lights. Chudzik wants to know “how we can use nocturnal flight calls as an indicator to examine collision risks in species.”

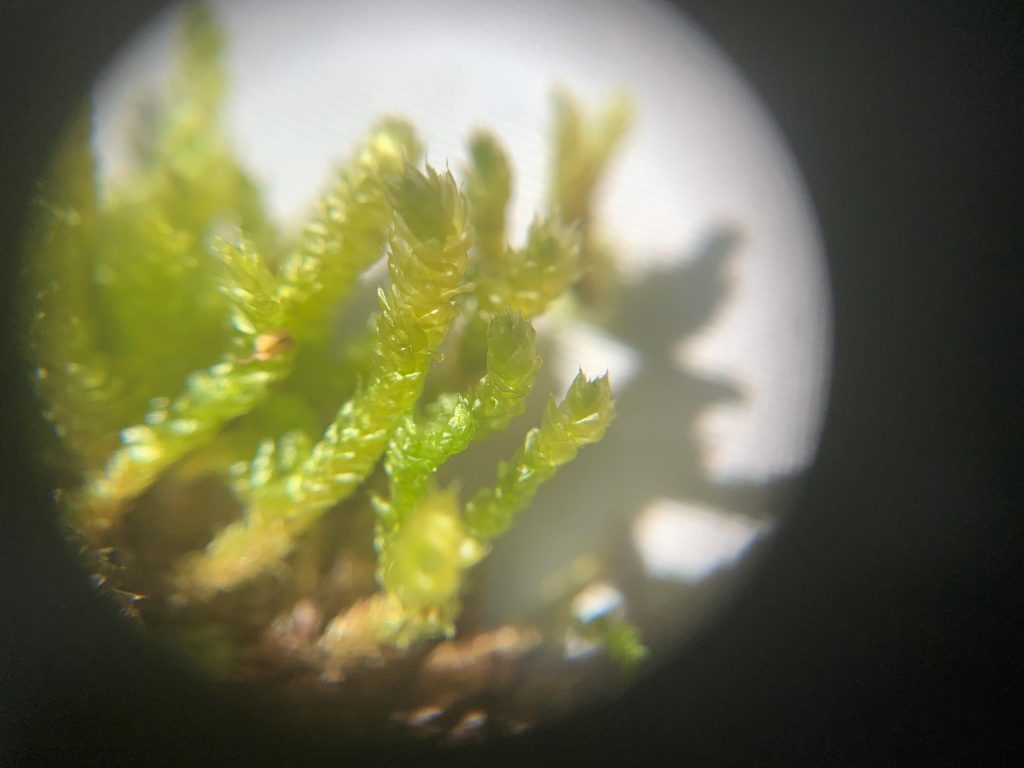

Image courtesy of Chudzik.

Previous research, Chudzik says, has identified a strong correlation between the number of flight calls recorded on a given night and the overall migration intensity that night. “If sparrows have a high number of detections, there is likely a high number migrating through the area,” Chudzik explains. But some species call more than others, and there is “taxonomic bias in collision risk,” with some species that call more colliding less and vice versa. Chudzik is exploring this relationship in her research.

Unlike bird songs, nocturnal flight calls are very short. The different calls are described with technical terms like “zeep” and “seep.” Chudzik is part of a small but passionate community of people with the impressive ability to identify species by the minute differences between their flight calls. “It’s a whole other world of… language, basically,” Chudzik says.

Image from Chudzik.

She began studying nocturnal flight calls for research she did as an undergraduate, but her current project no longer needs to rely on talented humans to identify every individual call. A deep learning model called Nighthawk, trained on a wealth of meticulous flight call data, can identify calls from their spectrograms with 95% accuracy. It is free and accessible to anyone, and much of the data it’s been trained on comes from non-scientists, such as submissions from a Facebook community devoted to nocturnal flight calls. Chudzik estimates that perhaps a quarter of the people on that Facebook page are researchers. “The rest,” she says, “are people who somehow stumbled upon it and… fell in love with nocturnal flight calling.”

In addition to studying nocturnal flight calls, Chudzik’s research will investigate how topography, like Lake Michigan by Chicago, affects migration routes and behavior and how weather affects flight calls. Birds seem to communicate more during inclement weather, and bad weather sometimes triggers major collision events. Last fall in Chicago, collisions with a single building killed hundreds of migratory birds in one night.

Chudzik had a recorder on that building. It had turned off before the peak of the collision event, but the flight call recordings from that night are still staggering. In one 40-second clip, there were 300 flight calls identified. Normally, Chudzik says, she might expect a maximum of about seven in that time period.

Nights like these, with enormous numbers of migrants navigating the skies, can be especially deadly. Fortunately, solutions exist. The problem often lies in convincing people to use them. There are misconceptions that extreme changes are required to protect birds from window collisions, but simple solutions can make a huge difference. “We’re not telling you to tear down that building,” Chudzik says. “There are so many tools to stop this from happening that… the argument of ‘well, it’s too expensive, I don’t want to do it…’ is just thrown out the window.”

What can individuals and institutions do to prevent bird-window collisions?

Turn off lights at night.

For reasons not completely understood, birds flying at night are attracted to lit-up urban areas, and lights left on at night can become a death trap. Though window collisions are a year-round problem, migration nights can lead to high numbers of victims, and turning off non-essential lights can help significantly. One study on the same Chicago building where last year’s mass collision event occurred found that halving lighted windows during migration could reduce bird-window collisions by more than 50%.

Chudzik is struck by “the fact that this is such a big conservation issue, but it literally just takes a flip of a switch.” BirdCast and Audubon suggest taking actions like minimizing indoor and outdoor lights at night during spring and fall migration, keeping essential outdoor lights pointed down and adding motion sensors to reduce their use, and drawing blinds to help keep light from leaking out.

Use window decals and other bird-friendly glass treatments.

There are many products and DIY solutions intended to make windows safer for birds, like window decals, external screens, patterns of dots or lines, and strings hanging in front of a window at regular intervals. For window treatments to be most effective, they should be applied to the exterior of the glass, and any patterning should be no more than two inches apart vertically and horizontally. This helps protect even the smallest birds, like kinglets and hummingbirds.

A 2016 window collision study at Duke conducted by several scientists, including Duke Professor Nicolette Cagle, Ph.D., identified the Fitzpatrick Center as a window collision hotspot. As a result, Duke retrofitted some of the building’s most dangerous windows with bird-friendly dot patterning. Ongoing collision monitoring has revealed about a 70% reduction in collisions for that building since the dots were added.

One obstacle to widespread use of bird-friendly design practices and window treatments is concerns about aesthetics. But bird-friendly windows can be aesthetically pleasing, too, and “Dead birds hurt your aesthetic anyway.”

If nothing else, don’t clean your windows.

Bird-window collisions don’t just happen in cities and on university campuses. In fact, most fatal collisions involve houses and other buildings less than four stories tall. Window treatments like the dots on the Fitzpatrick building can be costly for homeowners, but anything you can put on the outside of a window will help.

“Don’t clean your windows,” Chudzik suggests—smudges may also help birds recognize the glass as a barrier.

Window collisions at Duke

The best thing Duke could do, Chudzik says, is to be open to treating more windows. Every spring, students in Cagle’s Wildlife Surveys class, which I am taking now, collect data on window collision victims found around several buildings on campus. Meanwhile, a citizen science iNaturalist project collects records of dead birds seen by anyone at campus. If you find a dead bird near a window at Duke, you can help by submitting it to the Bird-window collisions project on iNaturalist. Part of the goal is to identify window collision hotspots in order to advocate for more window treatments like the dots on the Fitzpatrick Center.

Spring migration is happening now. BirdCast’s modeling tools estimate that 260,000 birds crossed Durham County last night. They are all protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. However, Chudzik says, “We haven’t thought to protect them while they’re actually migrating.” The law is intended to protect species that migrate, but “it’s not saying ‘while you are migrating you have more protections,’” Chudzik explains. Some have argued that it should, however, suggesting that the Migratory Bird Treaty Act should mandate safer windows to help protect migrants while they’re actually migrating.

Photo courtesy of Chudzik.

We can’t protect every bird that passes overhead at night, but by making our buildings safer, we can all help more birds get one step closer to where they need to go.

Post by Sophie Cox, Class of 2025