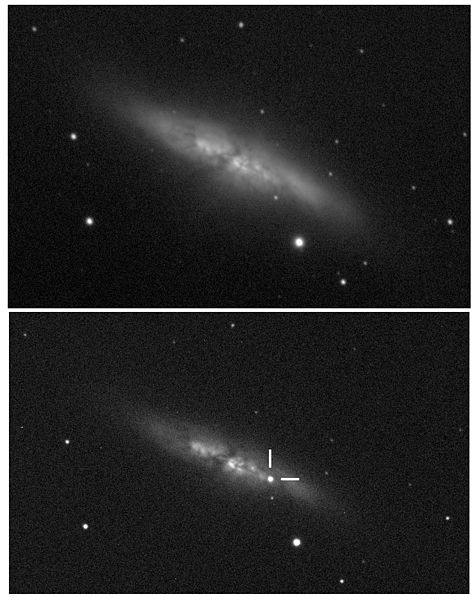

The M82 galaxy before (top) and after (bottom) its new supernova on Jan. 22 (Photo: UCL/University of London Observatory/Steve Fossey/Ben Cooke/Guy Pollack/Matthew Wilde/Thomas Wright)

By Erin Weeks

In the early morning hours of January 22, the Earth turned spectator to a celestial event the likes of which hadn’t been seen in nearly three decades. The explosive death of a white dwarf star in Messier 82 (M82), a nearby galaxy, quickly ignited the astronomy world.

The supernova is exciting for a number of reasons that other outlets have well outlined — but unfortunately for Kate Scholberg, neutrinos are not one of them. Scholberg, a Duke University physics professor, studies the mysterious, nearly-massless particles at Super-K, a detector located deep in the mountains of Japan. Super-K was designed to spot neutrinos as they speed through Earth, revealing information about their sources, which can include the sun, cosmic rays, and supernovae.

“M82 is too far away for us to see any neutrinos from it,” Scholberg wrote in an email. “It’s about 11.4 million light years from us, meaning that the chance of seeing even a single neutrino from a core-collapse supernova in current detectors is probably a few percent or less (of course, we’ll look).”

Even if it were close enough, she said, this supernova doesn’t appear to be the type that generates a lot of neutrinos. White dwarves are common, dense stars whose supernovae are triggered when they consume new matter and experience runaway nuclear reactions. It takes a far more massive star to undergo core collapse, when a star’s unstable center caves in under the its own gravity.

“Core-collapse supernovae are the ones that spew neutrinos,” she wrote. “So, not much hope we’ll see anything in neutrinos, alas.”

Scholberg coordinates SNEWS, the SuperNova Early Warning System, which will sound the alarm at the first sign of a neutrino-generating supernova. SNEWS and Scholberg will have to keep waiting for the next big blast, but the white dwarf supernova in M82 is still great news for physicists who study another hot topic — dark energy.

Astronomers spotted the supernova unusually early, meaning they’ll be able to collect a wealth of data before it hits peak brightness in a couple of weeks. It may be possible then to see the supernova with just a set of binoculars.

![A six-photo composite of the starburst galaxy M82 (Photo: NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team [STScI/AURA])](https://researchblog.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/ColorM82.jpg)