by Alyssa Granacki

Dante identifies Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a narrative poem containing over 250 myths, as an example of excellent poetry in De vulgari eloquentia: “And perhaps it would be most useful, in order to make the practice of such constructions habitual, to read the poets who respect the rules, namely Virgil, the Ovid of the Metamorphoses, Statius, and Lucan, as well as others who have written excellent prose…” [Et fortassis utilissimum foret ad illam habituandam regulatos vidisse poetas, Virigilium videlicet, Ovidium Metamorfoseaos, Statium, atque Lucanum…] (De vulgari eloquentia 2.6.7). In Inferno 4, Ovid appears again, as he does in the Vita Nuova, beside Virgil, Homer, Horace, and Lucan. Brunetto Latini, Dante’s mentor, names Ovid as the master of Love in his work, the Tesoretto (2364-9). Ovid was probably Dante’s primary mythological source, and the Comedy is peppered with references to the myths of the Metamorphoses: The details of Ulysses journey (Inf.26.90-106, Met. XIV.308, 435-440); the comparison of sinners in Malebolge to the sick population on the island of Aegina (Inf.29.58-65, Met.VII.501-660); Hecuba’s likeness to an angry dog (Inf.30.13-21; Met.XIII.819-829). The Neapolitan Ovid, a manuscript of the Metamorphoses created between eleventh and thirteenth centuries, is filled with vivid illustrations and robust commentary. In the page below, we can see the types of images that may have accompanied Dante’s reading of the poem.

Neapolitan Ovid. Illuminated manuscript on parchment. Eleventh to thirteeth century. Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli. © World Digital Library.

The Metamorphoses clearly influenced Dante’s punishment of the thieves in the Inferno (25.97-100). He silences Ovid as he describes their gruesome transformation into snakes: “Let Ovid now be silent, where he tells of Cadmus, Arethusa; /if his verse has made of one a serpent, one a fountain/I do not envy him” [Taccia di Cadmo e d’Aretusa Ovidio/ ché se quello in serpente e quella in fonte/ converte poetando, io non lo ’invidio].

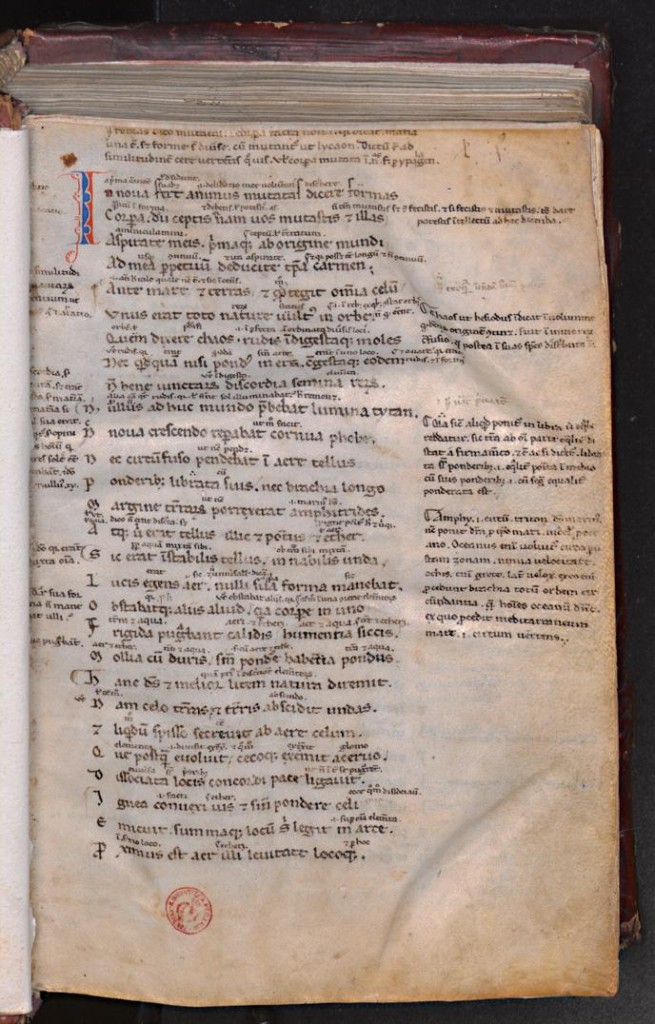

Robert Black has demonstrated how manuscripts of Ovid’s works attest to his canonical status. Ovid appears in Italian schoolbooks as early as the eleventh century. While ancient authors were employed less frequently in the thirteenth century, the study of Ovid appears to have persisted. A codex of the Metamorphoses from the turn of the fourteenth century contains glosses suggesting school use. In addition to commentary containing notes on mythology, grammar, and philology, early Trecento commentators also added allegorical glosses. Dante certainly would have been familiar with these commentaries, and like the allegorical commentators he read, he found a Christian purpose for the ancient pagan work.

Metamorphoses with commentary. Thirteenth century. Pluteo 36.05, fol. 1r. © Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana.

For an interactive look at intertextuality in Dante and Ovid, see the Digital Dante project.

Selected Bibliography

Black, Robert. “Ovid in Medieval Italy,” in Ovid in the Middle Ages, edited by Clark, Coulson, and McKinley. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Curtius, Robert Ernst. European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages. Translated by Willard R. Trask. New York: Bollingen Foundation; Pantheon Books, 1953.

Ginsberg, Warren. “Dante’s Ovids,” in Ovid in the Middle Ages, ed. Clark, Coulson, and McKinley. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Marchesi, Simone. “Distilling Ovid: Dante’s Exile and Some Metamorphic Nomenclature in Hell,” in Writers Reading Writers: Intertextual Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Literature. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007.

Paratore, Ettore. “Ovidio Nasone, Publio” in Enciclopedia Dantesca, 1970. Available via Treccani: http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/publio-ovidio-nasone_(Enciclopedia-Dantesca)/

Picone, Michelangelo. “Dante and the Classics” in Dante: Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Amilcare A. Iannuci. Tornoto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Sowell, Madison U., ed. Dante and Ovid: Essays in Intertextuality. Binghamton, New York: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, State University of New York at Binghamton, 1991.