Deeps > Representing Bois Caïman > Bois Caïman as “Religion” > Occupation and the Occult

By Lenny Lowe

“Voodoo” in U.S. Occupied Haiti

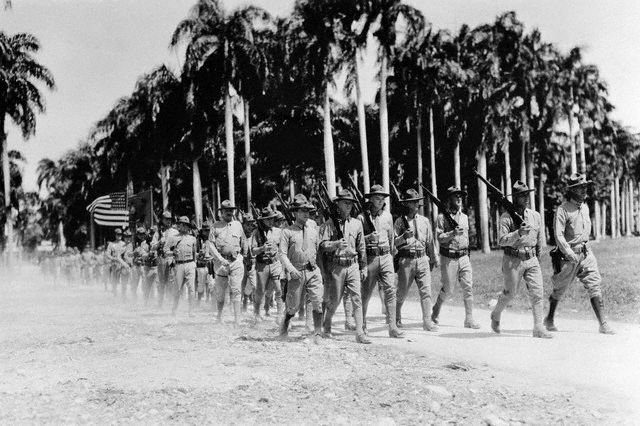

In July 1915, a mob killed President Vilbrun Guillaume Sam in retaliation for the massacre of 167 political prisoners. The event gave the U.S. government its justificatory pretext for a long planned military intervention, which itself “was part of a broader sweep of American intervention in the Caribbean” which began with Cuba and Puerto Rico in 1898.[1] The First World War increased concerns over German presence in Haiti, and the Haitian port of Môle Saint-Nicholas had become highly attractive for the refueling of U.S. Naval ships.[2] Furthermore, the U.S. had growing economic interests in Haiti as American interests had come to control the Banque Nationale of Haiti. The mob violence and political unrest in 1915 would mark the beginning of a 19-year occupation by U.S. military forces. Within a week of President Guillaume Sam’s murder, 1,100 U.S. marines arrived in Haiti.

The U.S. Occupation (1915-1934) would be characterized by “the imposition of martial law, press censorship, and efforts to alter the country’s legal apparatus.”[3] Kate Ramsey notes that perhaps even more than through the alteration of laws, the U.S. effected these changes “through the enforcement of selected Haitian laws, with opportunistic disregard for customary legal practice.”[4] Among those laws selected for enforcement were articles 405-407 of the Code Pénal that prohibited les sortileges. This was almost entirely understood by the U.S. military officials as a prohibition against the practice of what became Anglicized as “voodoo.”

A part of Ramsey’s argument in The Spirits and the Law (2012) is that Vodouizan (practitioners of Vodou) sometimes “insisted that marines apply article 405 in ways consistent with popular consensus about the just object of these laws (malicious magic), but antithetical to U.S. military rationales for enforcing them” (law and order and moral decency).[5] This helps to explain in part the apparent ambivalence of Haitians toward these laws, even when enacted by the U.S. military. However, the perhaps more significant impact of the U.S. Occupation on Vodou was the way this anti-“voodoo” campaign “played a key role in the construction, proliferation, and commoditized circulation of imperial images of Haitian ritualism during and after the occupation.”[6]

A significant part of this construction and proliferation involved an explicit racialization of Haitians and Haitian religious practice. Laurent Dubois reminds us that “All of the marines were white, and the brought ‘to the land of black people’ their own experiences and expectations from the racially segregated United States.”[7] This is important, for within Haiti, the battle over Vodou is much better understood as a struggle to control and marginalize the threat of a “parallel power” of the rural masses. But, the direct involvement of U.S. marines provides the context for a rapid racialization of Vodou on an international scale.[8]

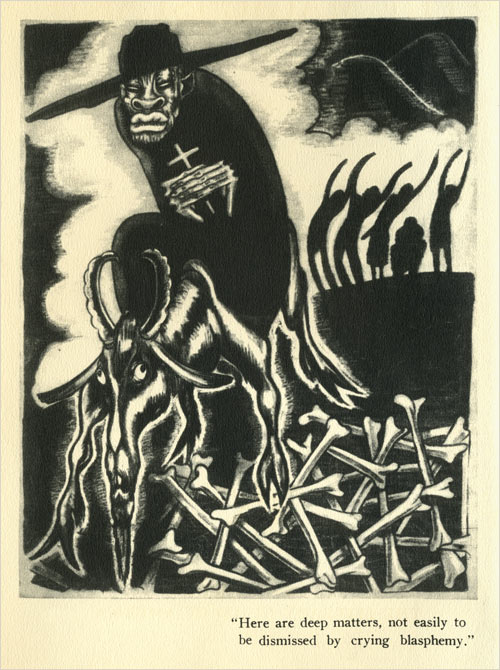

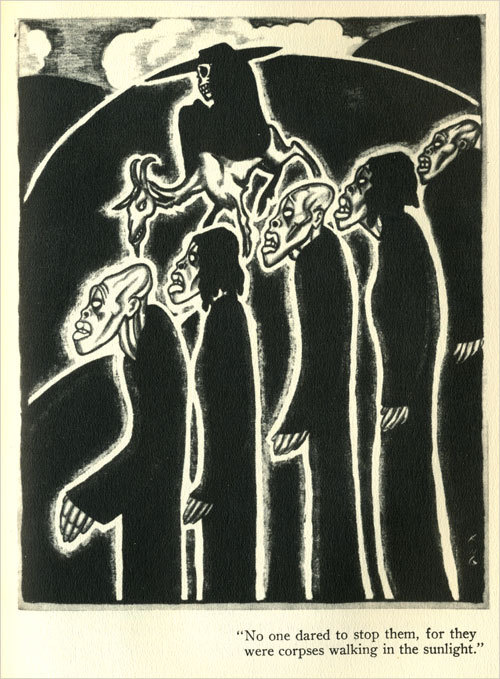

The Occupation also opened Haiti to the gaze of countless adventurers and journalists. Perhaps the most well known of the “imperial images” to be produced in this period comes from William Seabrook’s The Magic Island. Published at the end of the Occupation in 1929, Seabrook’s masterful but extravagantly exotic and sensationalized portrayal of Haitian Vodou seems to have depended quite heavily upon information from marine reports of temple raids.[9] The images accompanying the monograph attest to the intense racialization that characterized accounts of this period. He offered readers a glimpse at nighttime ceremonies of “sex-maddened saturnalia” and, perhaps most importantly, zombies.[10] The genealogy of the zonbi is a complicated both etymologically and as a cultural phenomenon. (Click here — Zonbiology — for my own take on the “science” of the Haitian zonbi.) What is certain, however, is that a good deal of cultural misunderstanding and misrepresentation has yielded the contemporary Hollywood variety that dominates today. In The Magic Island, Seabrook claims to be shaken to his core by an encounter with zombies, and he features a story about a man who used a band of zombified men to work at HASCO (the Haitian American Sugar Co.) and to steal their wages. As Dubois and others have noted, it is rather telling that Seabrook found his zombies at HASCO. Despite his apparent surprise at the story, the “zombie” laborers at HASCO were “probably a way for the local community to articulate the feelings evoked by the reappearance of the plantation in their midst.”[11]

Seabrook’s account would simply mark the beginning of a stream of zombies out of Haiti and onto movies screens, books, and magazines in America. It is a commoditized flow that has only increased in recent years, and it owes its existence to the racialized, exoticized “imperial images” that emerged with the U.S. Occupation of Haiti. The global image of “voodoo” and Haiti would never be the same.

Co-optation, Cultural Politics, and Terror

The U.S. Occupation also brought to Haiti an increasing number of Protestant missionaries for whom Vodou and Catholicism were a double-threat, and because of the ubiquity of both, were often assumed to be a singular problem.[12] Catholicism was understood by Protestants to be a poor attempt to veil what was nothing less than African witchcraft or even Satanism.

What transpired in this tense religious situation was a three-way battle in which Vodou was most often the primary target. The Catholic Church set out to extirpate Vodou through methods that resembled the early extirpation campaigns in 16th and 17th century New Spain. The campaign itself was made possible by the increased focus on existing laws (Article 405 in particular) that began with the U.S. Occupation. As Ramsey notes, however, the “negation of ‘superstition’ through this tightened penal regime produced the positive category of ‘popular dance,’ constructed by the state during the early 1940s as a sign of official national particularity.”[13] This kind of cultural politics would make possible the accounts of anthropologists like Melville Herskovitz, who portrays an entire cycle of Vodou ceremonies despite their illegal status at the time of his field work for Life in a Haitian Valley.

The ambivalence of Vodou during this period – as both illegal and a marker of Haitian cultural nationalism – would be put to particularly pernicious use during the regime of “Papa Doc” Duvalier. Though many have made much of Papa Doc’s use of Vodou imagery – in particular, his supposed evocation of the image of Baron Samedi – Dubois points out that his use of Vodou and Catholicism alike were always strategic co-optations. In addition to the years of terror and violence, rapes and murders, the Duvalier era of Haitian history would only serve to further implicate Vodou in the production of Haiti’s “problems.”

In sum, the period of U.S. occupation in Haiti produced a decisive shift in perceptions of Vodou. Whereas it had once symbolized African primitiveness, a threat to progress and civilization, and a parallel political power, it now came to be associated with criminality, violence and the occult, even as Haitian leaders attempted to coopt Vodou for the purposes of dictatorial terror or cultural politics.

[1] 1. Laurent Dubois, Haiti : The Aftershocks of History, 1st ed. (New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Co., 2012) 211.

[2] Ibid.

[3] 1. Kate Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law : Vodou and Power in Haiti (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011) 120.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 121.

[7] Dubois, 226.

[8] I do not mean to suggest that race was not a significant factor in the 19th century. Indeed, the refusal of European and American powers to recognize Haiti’s independence was at least partly based on racialized understandings of the incapacity of Africans for self-government. However, the end of the 18th century had seen an intensification of biological racism based on Darwinian notions, and especially so in the U.S.

[9] Dubois, 297.

[10] William Seabrook, The Magic Island (New York: The Literary Guild of America, 1929).

[11] Dubois, 298.

[12] Of course, Vodou and Catholicism in Haiti do depend upon one another, as often practiced together and constitute a double-identity for many. But, it would also be wrong to suggest that all Vodouizan are Catholic and vice versa.

How to cite this article: “Occupation and the Occult,” Written by Lenny J. Lowe (2014), Deeps, The Black Atlantic Blog, Duke University, http://sites.duke.edu/blackatlantic/ (accessed on (date)).