by Sandie Blaise

Deeps > Representing Bois Caïman > Music and Bois Caïman > Bois Caïman as a symbol of resistance

Haitian musicians have always played the role of journalists and historians, documenting the country’s history and helping to shape its path forward. Whether expressing through Vodou rhythms, or voicing political frustrations and daily difficulties of through the Troubadou and Racine traditions, music has always been at the core of Haiti’s identity. (Lakou Mizik)

“Mizik rasin” and the re-appropriation of vodou symbols in the cultural revolution

“Mizik rasin” or the Haitian grass-root music is the style in the Haitian music landscape that better captures the use of Bois Caïman as a tool of resistance. It is part of a bigger movement; the “mouvman rasin” or roots movement that Jayaram defines as “a social and cultural movement that started in the 1970s in response to perceived threats to Haitian identity in response to Duvalierism and to international sources, involving various but not all groups of the Haitian population” [1. Kiran Jayaram, “The Politics of Culture in the Mouvman Rasin in Haiti,” Occasional Papers in Haitian Studies, no. 29, Bryant C. Freeman, ed. Institute of Haitian Studies, University of Kansas, 2004, p. 32.]

Ethnomusicologist Gage Averill describes the musical aspects of mizik rasin as “neo-traditional music” trying to “evoke through incorporation something of the music sound and ethos of the traditional models.”[2. Gage Averill, “Se Kreyòl Nou Ke/We’re Creole: Musical Discourse on Haitian Identities,” Music and Black Ethnicity: The Caribbean and South America. G.H. Béhague, ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1994, p. 172.] Some of the first bands with a revolutionary goal that were created in the 1970s and 1980s are called Foula, Sanba Yo and Boukman Eksperyans – the most commercially successful of the three [see this page in French for a complete discography].

Since the movement emerged while the Duvalier totalitarian regime was ruling Haiti and was precisely against it, one may wonder how such a movement could ever emerge in such a dictatorship, let alone develop. The main answer is to be found in its link with the vodou religion that had been appropriated by the government and had become symbolically linked with violence through the brutality of the regime and more particularly the actions of the “tontons macoute” who formed the Haitian paramilitary force.

By using vodou elements, mizik rasin actually took advantage of the regime’s sympathy to the vodou religion and avoided repression or censorship while re appropriating it as part of the Haitian culture. For Haitian journal Bon Nouvèl, “this roots music is a contemporary artistic manifestation of Vodou, a religion that has been historically discouraged by both the Haitian government (except for its dubious use by Francois Duvalier) and Christians, both Protestants and the Catholic hierarchy.”[6. “Veritab mizik rasin nan se yon zouti chanjman!,” Bon Nouvèl, 1994, p. 10-14.] Jayaram recalls that in the summer of 2002, Boukman Eksperyans performed at concerts with “multiple singers, two to four drummers of either a drum set or on Vodou drums, an electric bassist, an electric guitarist, a multi-keyboard player, and dancers. The drummers would play some Vodou rhythms. (…) Roots groups inside of Haiti, like Kanpech, Boukan Ginen, Tokay, and Chanddl, as well as groups outside of Haiti, like Azaka (with Roots pioneer Azoukc Sanon) and the Swedish group Simhi, have shared this type of instrumentation. Other groups have different instrumentation. Sanba Zao, perhaps the earliest of the Roots music pioneers, and the group Djakata have a different set up.” [7. Jayaram, p. 39-40]. For others, real mizik rasin is the music of a Vodou ceremony: “[it] is two drums, a Vodou song leader, a rattle, and everyone’s djaye.”[8. Edelle interviewed by Jayaram in 2001. See Jayaram, p. 40]

Jayaram writes that during some performances, members of Boukman Eksperyans “would wear blue denim shirts and rolled up pants” drawing upon “the image of a traditional Haitian rural inhabitant or the peasant spirit of agriculture, Azaka,”[9. Jayaram, p. 79] hereby re appropriating this element that had been associated to and subverted by tonton makout who wore the same piece of clothing.

In this cultural revolution, the references to the Bois Caïman ceremony also acted as re appropriation of vodou symbols, the participants’ wish to shed a positive light on the traditional religion, and their use of historical revolutionary references as incentives in a fight whose social and cultural goals were somewhat similar.

To hear about the history of mizik rasin from one of its most influential musicians, watch this interview that Louis Lesly “Sanba Zao” Marcelin gave to the University of Miami radio station in 2012.

For a description of some of the mizik rasin bands aforementioned, Marguerite “Ezili Dantò” Laurent’s blog is very useful.

Kiran Jayaram also provides a discography of rasin and related music.

Boukman Eksperyans

Boukman Eksperyans was founded in Port-au-Prince in 1978 by Theodore “Lolo” Beaubrun, Marjorie Beaubrun, Daniel Beaubrun and Mimerose Beaubrun. The band incorporated elements of Haitian vodou into their music, and became famous in 1990 with the song “Kè m pa sote” (meaning “I’m not afraid”, or, more literally, “my heart doesn’t leap”) which protested against the post-Duvalier interim military government of General Prosper Avril.

Their firt album, released in 1991, was called “Vodou Adjae” after a vodou ceremonial dance. Here is what was written on the inside jacket of the CD:[3. See “Vodou Adjae” on Wikipedia.]

For thirty-five years, compas was the rhythm and the music to which Haiti danced. But in 1989, BOUKMAN EKSPERYANS introduced a revolution in Haitian music that helped to revitalize interest in Haiti’s traditional culture and religion (Vodou). Their particular brand of dance music, Vodou Adjae, bridged the dancefloor and the Vodou temple, mixing influences from religious drumming and from the high-energy springtime festival called rara.

Their message of unity, concern for Haiti’s impoverished peasants, and intolerance for political corruption and neglect struck a chord with a country seeking identity and direction after a long period of political strife. The message was transmitted through an irresistible beat and BOUKMAN EKSPERYANS won both the contest for best song in Haiti in 1989 as well as the public imagination (and the sense of frustration with recent political events) is unmatched in modern Haitian history.

BOUKMAN was the slave leader who helped to launch the revolution that led to the overthrow of French colonialism and the birth of the first black republic in the world in 1804. BOUKMAN was also a priest of the new Afro-Haitian religion called Vodou that helped to unify the Haitian slave to carry out the revolution. BOUKMAN EKSPERYANS captures the experience embodied in the image of BOUKMAN: a blend of African and Christian spirituality, stubborn resistance to oppression, and a fierce pride in the people, history and culture of Haiti.

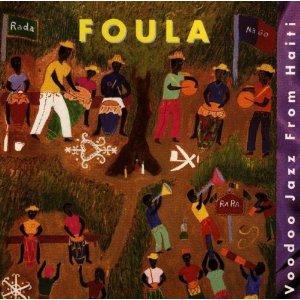

Foula

“Foula” (which later became “Foula Vodoule”) is one of the two groups that came out in 1984 of “Group Sa;” a band founded by Tido Lavaud, Chico Boyer, Doudou Chancy, Jean Robert Bernadotte and Nazaire Jean Baptiste that was the first roots band to perform in Haiti in 1980 or 1981.[4. See Marguerite “Ezili Danto” Laurent’s page] “Group Sa” never officially recorded any of its music, though. “Foula” released its first and only eponymous album “Foula” in 1995 and combined Vodou elements with jazz, creating “Vodou Jazz.” However, according to Jayaram, “this was not the same as the Vodou-Jazz of the 1940s” but “this new form of Vodou and Jazz more closely resembled what it would be like if Archie Shepp played with rural Haitian musicians.”[5. Jayaram, p. 40-41.]

Louis Lesly Marcelin (“Sanba Zao”)

Bois Caïman and Bookman’s invocation as symbols of resistance

In more recent times, the Afro-Caribbean hip hop group The Welfare Poets referred to the Bois Caïman ceremony in one of their songs. Founded at Cornell University at the beginning of the 1990’s, the band released their first album “Project Blues” in June 2000, and their second in 2005, entitled “Rhymes for Treason,” in which they mention Bois Caïman.

In the song “Sak Pase” (“What’s up?” in Haitian Creole), they sing in Haitian Creole and English about Haiti and the Haitian Revolution, Bois Caïman and Boukman. They also reiterate the Vodou priest’s invocation in the KiKongo language: “E, e, Mbomba! Kanga Bafyòti. Kanga Mundele. Kanga Ndòki. Kanga li!” (go to 2:05).

Marguerite “Ezili Danto” Laurent gives a translation of this invocation on her website: “The Supreme Creator (E, e, Mbomba, e, e!), Master of Breath shall foil the black collaborators/traitors (kanga bafyòti). Kill/stop the tyrannical white settlers/blan strangers (kanga mundele). Bind all evil forces/sorcerers (kanga Ndòki). Stop them!”

See the rest of the lyrics below, retrieved and edited from Viviane Saleh-Hanna’s PhD dissertation on Lyrical Passages Through Crime: An Afrobeat, Hip Hop and Raggea Production, featuring black criminology, 2007, pp. 246-247. Preview available on google, and whole dissertation on ProQuest. (References to the ceremony and to the spirit of resistance are in bold, my translation in italics)

The Welfare Poets – Sak Pase (2005)

[Chorus]

Sak pase? Sak pase tout moun ayisyen, sak pase?

What’s Up? What’s up Haitians, what’s up?

N ap boule! N ap boule, n ap boule monchè, n ap boule!

It’s all good! It’s all good, my friend, it’s all good! (“Boule” also means “to burn” so the literal sense is “We’re burning”)

Libète! Nou bezwen libète pou peyi mwen!

Liberty! We need liberty for my country!

Ayiti… Ayiti cheri

Haiti… Dear Haiti

Ankò!

Again!

Sak pase? Sak pase, sak pase, sak pase tout moun?

What’s up? What’s up, everyone?

N ap boule! N ap boule, n ap boule, n ap boule! I’m hot!

It’s all good!

Libète! Libète pou pèp mwen avèk peyi mwen!

Liberty! Liberty for my people and my country!

Ayiti… Ayiti cheri mwen

Haiti… My dear Haiti

Ankò!

Again!

Haiti

You’re hot like a plantation on fire

Set ablaze by Boukman

A hundred thousand slaves and those unafraid who heard through the wire

You inspired Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner

Countless rebellions with machetes and burners

Maroons on then they all won take a ….

Choppin’ the arms of state bastards

And all step out sound the alarms when they had to

Black pearl, unfurl your flag of hope

Black pearl, white fangs still clutch your throat

Black pearl, you inspired the world

Black pearl, you’re still a black pearl to me

E, e, Mbomba!

Kanga Bafyòti.

Kanga Mundele.

Kanga Ndòki. Kanga li!

Sak Pase? N ap boule! Libète Ayiti!

[Chorus]

Sak pase? Sa k ap fè, tout moun ayisyen, sa k ap fè?

What’s Up? What are you doing, Haitians?

N ap boule! N ap boule, n ap boule, n ap boule monchè!

It’s all good! It’s all good, my friend!

Libète! Nou bezwen libète pou peyi mwen!

Liberty! We need liberty for my country!

Ayiti… Ayiti cheri

Haiti… Dear Haiti

Chante!

Sing!

Sak pase? Sak pase, sak pase, sak pase tout moun?

What’s Up? What’s up, everyone?

N ap boule! N ap boule, n ap boule, n ap boule! I’m Hot!

It’s all good!

Libète! Libète pou pèp mwen avèk peyi mwen!

Liberty! Liberty for my people and my country

Ayiti… Ayiti cheri mwen

[Haiti… My dear Haiti]

And the spirit of Mackandal in Bwa Kayiman

Voodoo ceremony

Initiating Haitian liberation

Washin’ waters… there’s no attainment

Tryin’ to orchestrate this coup against their nation

Through political isolation

And economic asphyxiation

Aristide was destabilized

He wouldn’t agree to privatization

That’s when the US, IMF came with sanctions of land…

The CIA organized land orders and merchants

Under group 184 and convergence

Trained illegal insurgents

Puttin’ murderers back into service

Papa Doc lynch men… henchmen

To which the media was wordless

But the people of Haiti are resilient

Their future like their past will be brilliant

Black Jacobins be smashin’ the myth of white supremacy

Broke their legacy and destiny

It’s time for Dessalines

[Chorus]

Want to cite this page?

“Bois Caïman as a Symbol of Resistance,” Written by Sandie Blaise (2014), Representing Bois Caïman, The Black Atlantic Blog, Duke University, http://sites.duke.edu/blackatlantic/ (accessed on (date)). – See more at: http://sites.duke.edu/blackatlantic/sample-page/storytelling-and-representation-of-bois-caiman/music-and-bois-caiman/symbol-of-resistance/

hello,

what an fantastic blog. such a writing skills are awesome. I like this post so much. Thank you for sharing this post to us Gppr staffs. I definitely enjoying every little bit of it I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post nice post, thanks for sharing.

thanks

Yes, THANK YOU!! For this beautiful and beneficial recovery, reconstruction of our renewal of ourselves, our culture, and our renewed historical journey home…..